Relevant for General Studies

Bt cotton helped India become the world’s No. 2 producer and No. 2 exporter of the fibre. But those gains are now under threat

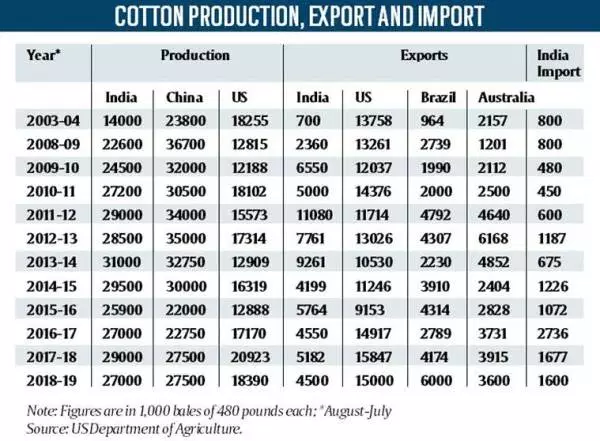

- Between 2003-04 and 2011-12, India’s cotton output more than doubled from 14 million bales (of 480 pounds or 218 kg each) to 29 million bales. In 2003-04, India was the world’s third largest cotton producer (behind China and the US) and seventh biggest exporter (after the US, Uzbekistan, Australia, Greece, Brazil and Burkina Faso), with its imports (0.8 mn bales) actually exceeding exports (0.7 mn bales).

- In 2006-07, India overtook the US to become the world’s No. 2 producer. It also emerged the No. 2 cotton exporter, though its shipments, at 4.875 million bales, were way behind the US’s 12.959 million. By 2011-12, not only was the country’s output almost twice that of the US (29 mn bales versus 15.573 mn), even its exports nearly matched the latter’s (11.08 mn bales versus 11.714 mn).

- India’s cotton production peaked at 31 million bales in 2013-14. In 2015-16, it displaced China as the top producer of the fibre, which, however, had more to do with the latter’s output registering a much steeper decline than India’s. In the current cotton marketing year (August-July), China has re-emerged as the world’s No. 1 producer. India’s estimated output for 2018-19 is four million bales below the peak of 2013-14 and its exports of 4.5 million bales a fraction of the 11 million-plus bales achieved in 2011-12. The country’s projected shipments this year are below that of the US and even Brazil (see table).

- The above numbers describe, in a nutshell, India’s journey from a net importer of cotton to turning into the globe’s second largest exporter and biggest producer — in just over a decade. They also capture the stagnation and setback in the more recent period, which has seen the country losing its numero uno position in production and being pushed to No. 3 in exports.

- The boom in production and exports during 2003-04 to 2013-14 had partly to do with global prices. As these surged from an average of 62-63 cents per pound (for American Upland varieties) in 2003-04 to 105.4 cents in 2010 and 155.7 cents in 2011, the value of cotton shipments from India, too, rose from a mere $ 205.08 million in 2003-04 to $ 4.33 billion in 2011-12. They remained relatively high at $ 3.75 billion and $ 3.64 billion in the subsequent two fiscals as well, with prices hovering around the 90-cents level.

- But the real impetus, no doubt, came from Bt technology, which helped the country to more than double production and take advantage of rising international prices.

- Indian farmers planted genetically-modified (GM) cotton hybrids — incorporating a single ‘cry1Ac’ gene isolated from the soil bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis or Bt and coding for a protein toxic to the American bollworm insect pest — first in 2002. In 2006, a second-generation Bollgard II cotton, also based on the US life sciences giant Monsanto’s proprietary technology, was launched. The Bollgard II hybrids contained an additional ‘cry2Ab’ Bt gene, intended to confer more effective resistance to a range of bollworm pests.

- Thanks to Bt technology, average cotton lint yields in India went up from 302 kg per hectare in 2002-03 to 566 kg in 2013-14, along with expansion in crop area from 7.67 million to 11.96 million hectares during this period.

- Two things have taken place since then. The first is global prices crashing to 70-75 cents in 2015 and 2016, leading to a plunge in India’s cotton exports to $1.90 bn in 2014-15, $1.94 bn in 2015-16 and $ 1.62 b in 2016-17.

- Second, no new technology. In 2014-15, when cotton area in the country peaked at 12.85 million hectares and the share of Bt hybrids reached 93 per cent, the effects of infestation, from pests hitherto considered ‘secondary’ to the American bollworm, began to show up. The Bt cotton based on Monsanto’s existing technologies were found to be susceptible, especially to the pink bollworm (mainly in Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh) and whitefly (in Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan). The damage from these so-called secondary pests was evidenced by average per-hectare yields dropping to 511 kg in 2014-15 and 484 kg in 2015-16, before recovering a tad to 542 kg in 2016-17 and 507 kg in 2017-18.

- But worsening matters has been a less-than-conducive environment for introduction of technology, in marked contrast to the last decade: The first-generation single-gene Bollgard technology was approved by the NDA regime of Atal Bihari Vajpayee, while commercialisation of Bollgard II happened under the first Congress-led UPA government. Both UPA-2 and the current NDA dispensation have displayed outright hostility to GM crop breeding, be it Bt brinjal or even a publicly-developed hybrid mustard technology.

- In July 2016, Monsanto withdrew its application for commercial cultivation of a third-generation Bollgard II-Roundup Ready Flex cotton in India. This cotton incorporated both the ‘cry1Ac’ and ‘cry2Ab’ Bt genes and a third ‘cp4-epsps’ gene from another soil bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens, which produces a modified protein that allows the plant to tolerate application of glyphosate herbicide.

- The decision to pull out the technology — enabling farmers to spray glyphosate that is not possible in normal cotton, where the chemical cannot distinguish between weeds and the crop itself — was motivated by two developments. In December 2015, the Agriculture Ministry issued a Cotton Seeds Price (Control) Order, empowering the Centre to “fix and regulate” the royalty/trait value charged by a GM technology supplier from seed companies that have incorporated it into their hybrids. This was followed by a draft notification in May 2016, obliging technology developers to licence their proprietary GM traits on demand.

- Between 2016 and the ensuing 2019 planting season, the maximum sale price of Bollgard II cotton seeds has been reduced from Rs 800 to Rs 730 per 450-gram packet, with the trait value payable on the technology, too, slashed from Rs 49 to Rs 20. The point to note is that farmers use about 1.5 packets per acre, whose cost, at Rs 1,100 now, works out to not even a tenth of the estimated total cultivation expense of Rs 15,500 for rainfed cotton. The latter includes cost of land preparation (Rs 2,200 per acre), sowing (Rs 600), fertiliser (Rs 4,100), weeding (Rs 3,200), insecticides (Rs 1,800) and picking (Rs 2,500 for kapas yield of 5 quintals). The ratio is even lower for irrigated cotton, where the total cost comes to roughly Rs 24,000 per acre — including for fertiliser (Rs 6,200), irrigation (Rs 1,000), weeding (Rs 6,000), insecticides (Rs 2,500) and picking (Rs 4,000, taking higher yield of 8 quintals).

- The question to ask is: When the key to boosting crop yields lies in genetics — we have definitely seen it vis-à-vis cotton — does arbitrary fixing of sale price and technology fee for seed make sense, more when it accounts for a minor share of the farmer’s own cultivation cost? This is a call the government that comes in next will have to take. For, at risk are not just the gains of the previous decade, but the country again turning a net cotton importer.