Women Employment in India – Lower Entry and Higher Exit Rates

(No 1 Sociology Optional Coaching)

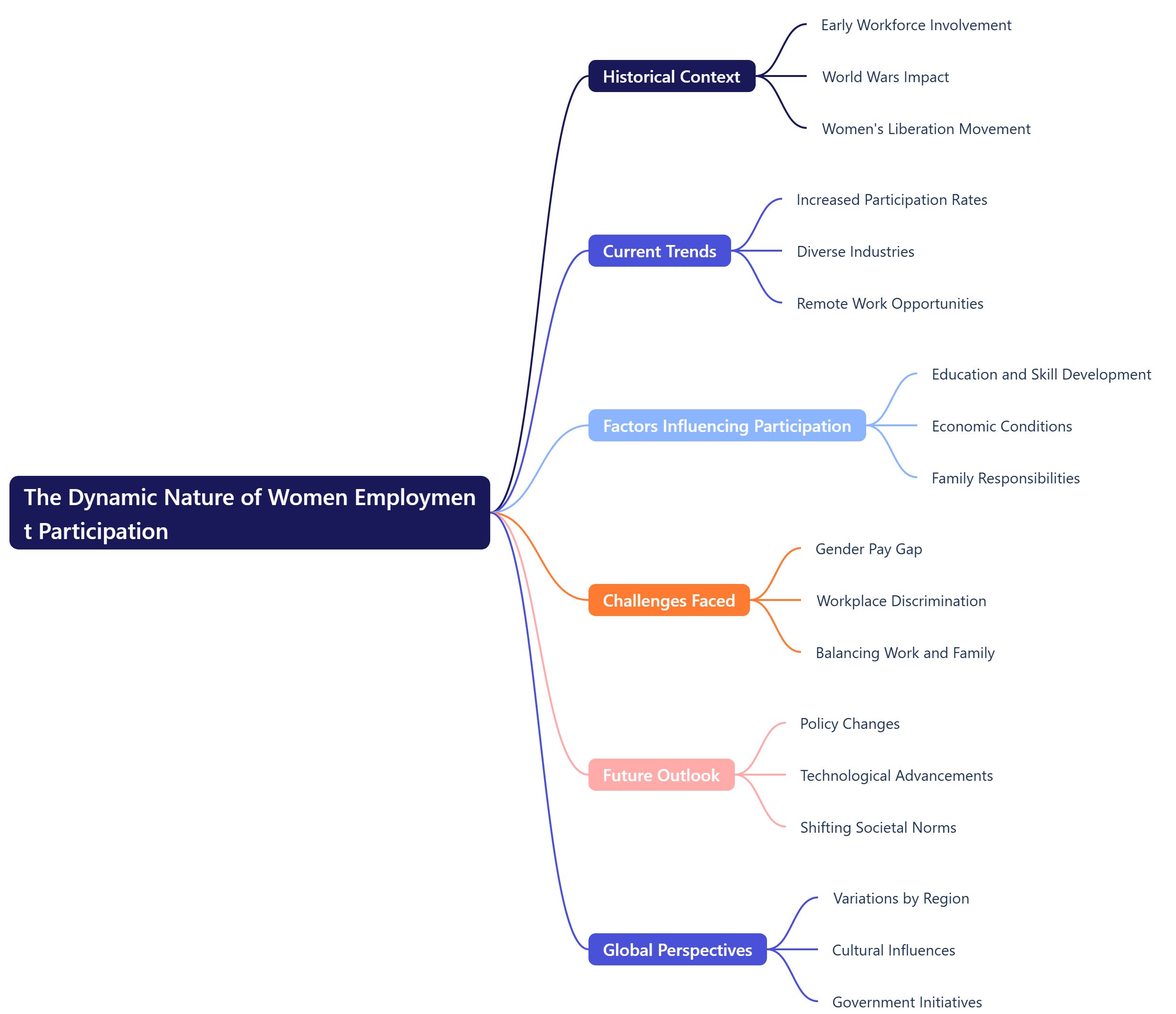

Women Employment in IndiaIndia’s low female labour force participation has often been explored in recent literature, but not enough focus has been given to the dynamic nature of employment, which involves individuals moving in and out of the workforce over time. By examining India Human Development Survey data from 2004-05 and 2011-12, it’s evident that women have lower entry rates and higher exit rates compared to men, both in the short and long term. Recent studies show that the female labour force participation rate (FLFPR) in India has not increased over the past two decades. National Sample Survey data from 1984-2012 reveal a decline in rural FLFPR, while urban FLFPR has remained stable. This is unexpected since economic prosperity, a decreasing gender gap in education, and a falling fertility rate should have led to increased participation. This stagnation or decline has prompted extensive research. On one side, discussions have focused on identifying the reasons behind this trend, as outlined in Stephan Klasen’s I4I post. On the other side, studies like those by Deshpande and Kabeer (2019) have questioned the accuracy of measuring women’s work, suggesting that their economic activities may not be fully captured in existing surveys. The Dynamic Nature of Women Employment Participation

An often overlooked aspect in current literature is that labour force participation (LFP) is dynamic, with individuals entering and exiting the workforce at different times. This is particularly significant for women who engage in various short-term activities in the labour market. To truly understand women’s work, it’s essential to track their activities over time, which requires panel data—information on the same individuals across multiple time points. Most existing studies analyze aggregate trends and determinants using repeated cross-sectional data, which doesn’t allow for investigating who is entering or exiting the workforce. In new research, we examine the dynamics of employment status for working-age women in India using nationally representative data from the India Human Development Survey (IHDS) that collected information on the same individuals in 2004-05 and 2011-12 (Sarkar, Sahoo, and Klasen 2019). This panel dataset enables us to estimate the rates and determinants of labour market entry and exit for women in India. It’s important to differentiate between continual (persistent) employment status (either employed or unemployed) and transitory employment, as they have different policy implications. For instance, those continuously out of the labour force may need to challenge social norms to enter, while those already employed may need supportive policies to sustain their employment. Additionally, LFP decisions can exhibit intertemporal dependence, meaning participation in the current period may be influenced by the previous period’s status. Employment involves costs such as job search and, for women, overcoming cultural barriers within their families and society. Conversely, being employed can empower women by raising their aspirations, preference for independence, or expected consumption standards. Thus, the factors driving the decision to enter the labour force may differ from those influencing the decision to exit. Women Employment Entry and Exit RatesTo estimate employment transitions, the sample focuses on women aged 25-55 in 2005, with a follow-up in 2012. The entry rate is defined as the proportion of women who became employed by 2012 out of all women who were not employed in 2005. Similarly, the exit rate is defined as the proportion of women who left employment by 2012 out of all women who were employed in 2005. In 2005, about 50% of the women in the sample were employed. Over the next seven years, 21% of these women exited employment. In comparison, 90% of men in the sample were initially employed in 2005, and only 6.7% of them were no longer employed by 2012. This indicates that women not only have a lower participation rate but also a higher exit rate than men. Among the women not employed in 2005, only 25% were employed by 2012, whereas the entry rate for men was 52%. Thus, between the two survey rounds over seven years, women were three times more likely to exit employment and half as likely to enter employment compared to men. The figures are particularly stark for urban areas, where only 24% of women were employed at the baseline, with an exit rate of 29% and an entry rate of 13%. Factors Affecting the Dynamics of Women’s Employment Status

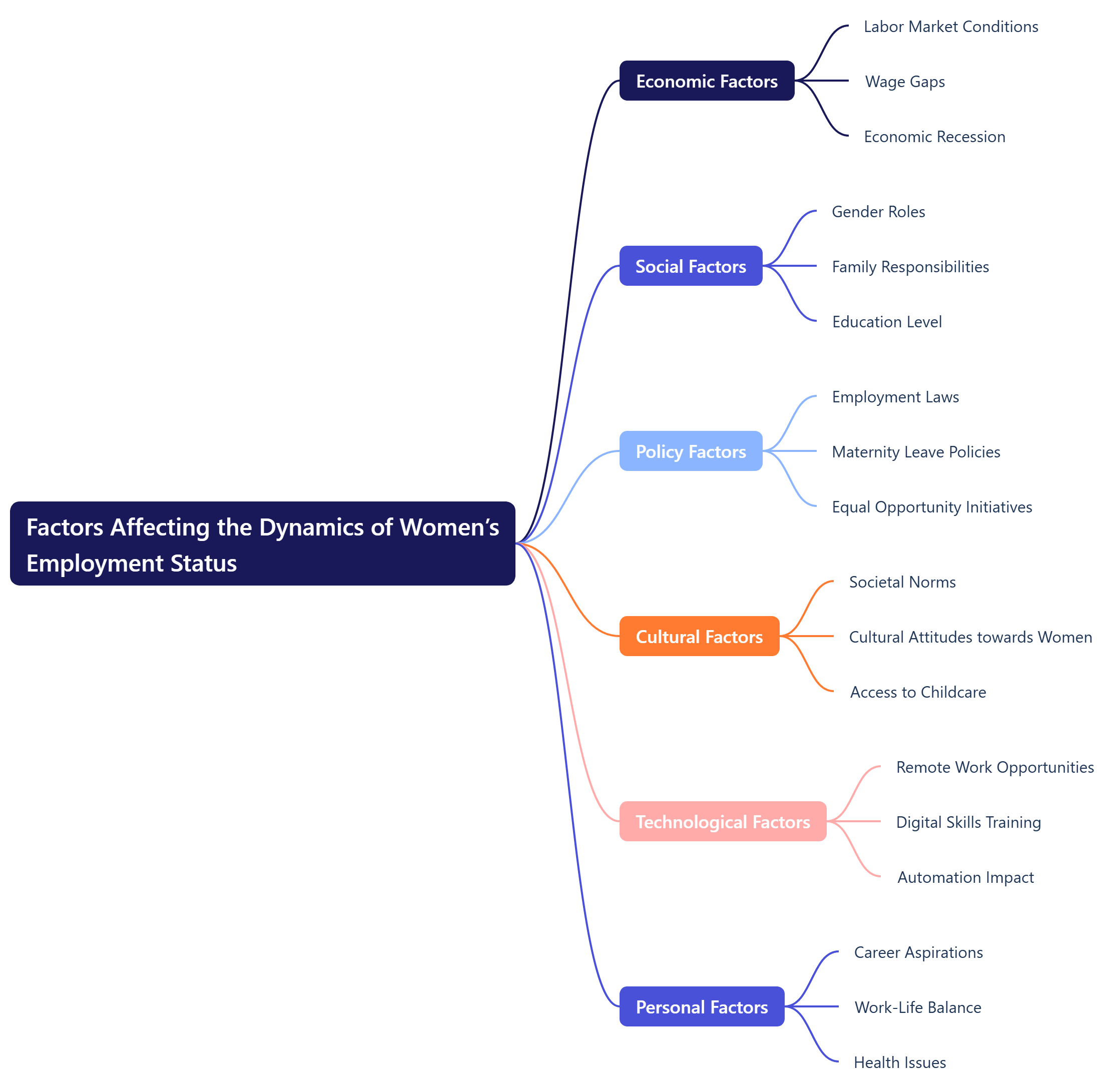

Our analysis shows that women experience significant transitions in their employment status, indicating a lower attachment to the labour market compared to men. We also identify various factors influencing women’s decisions to enter or exit employment and test if the same factors affect both entry and exit. Using panel data, we examine the impact of both baseline characteristics and factors that change over time. For example, having a newborn child between the two survey rounds increases the probability of exiting employment by 3 percentage points. The exit rate also rises if an elderly member (above 65 years) joins the household, suggesting women may leave their jobs to care for children and elderly family members. Interestingly, if the mother- or father-in-law lives with the family, women are less likely to leave their jobs, possibly because the in-laws share household responsibilities, enabling women to continue working. However, these factors do not influence women’s entry into employment. We find that a household’s financial status significantly impacts women’s decisions to enter and exit employment. If other household members’ assets or income increase, women are less likely to enter and more likely to exit the workforce. This suggests women are seen as secondary earners who participate in the labour market only when needed to supplement household income. Similarly, higher entry and lower exit rates are observed among women from disadvantaged castes and households where male members have low education levels. Local economic development also encourages entry and reduces exit, likely by increasing labour demand, particularly in the southern states. As a policy-relevant factor, we explore the impact of the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA). The intensity of MNREGA implementation significantly reduces women’s exit rates from the workforce but has no effect on women’s entry. Since MNREGA provides unskilled manual labour at minimum wage, it may not attract women who are not used to such work. However, by expanding employment opportunities, MNREGA helps those already in the workforce to continue participating. In addition to MNREGA, other factors like education, household wealth, household size, education of male members, changes in the number of elderly members, and new births have different effects on entry and exit. Thus, our analysis indicates that the factors influencing entry and exit decisions are not symmetrical. Women Employment in India: Increasing Importance of Analysing TransitionsThe IHDS data, collected over two rounds seven years apart, primarily enables the analysis of long-term transitions. However, what about shorter-term changes? Utilizing the 2017-18 Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), which is a panel dataset, we can estimate transitions across quarters within the same year for urban areas. We find that about 24% of women (compared to 92% of men) are in the labour force in a given quarter. Over 10% of these women exit the labour force in the next quarter, whereas only 1% of men do. Among the women who exit, approximately 70% remain out of the labour force even in the subsequent quarter. Therefore, both short- and long-term exit rates from employment among women are notably high. The Covid-19 pandemic has intensified research focus on the issue of exiting and returning to employment. Our study highlights that, even under normal circumstances, women’s attachment to the labour market is much lower than men’s—they are more likely to exit and less likely to re-enter. While low FLFPR is a major concern, it is also crucial to consider the women who overcome barriers to enter the labour market only to leave at a high rate. Notes:

|

To Read more topics like Women Employment in India, visit: www.triumphias.com/blogs.

Read More Blogs:

Courtesy : Soham Sahoo (Indian Institute of Management Bangalore) , Sudipa Sarkar (University of Warwick).