Sociological about a Pandemic

(Relevance For Sociology Optional Civil Services Exam)

Conceptualising a New Sociological pandemicABSTRACT: Over the last year, the entirety of the world was made to come to an unprecedented stand-still. Naturally, plenty of attempts have been made to understand the nuances of this event called the COVID 19 pandemic from the lens and purview of social institutions such as the scientific, technological, medical and public health entities. While there has rarely been a dearth of discourses dealing with the social, political and cultural implications of a pandemic, they are either limited to a niche academic sphere or they do not get the societal attention that they very well deserve. This article will humbly attempt to address both, the inaccessibility of a sociological discourse on pandemics and also the indifference it faces in society, primarily from the above-mentioned social institutions. When one traces the development of human society from the Enlightenment period until now, the dominating dialogue in society is inevitably derived from the scientific community, foregrounding the power-relationship between natural or exact sciences and social sciences. However, in an attempt to preach objectivity and rationality, scientific communities tend to lose out on the value of a sociological analysis that may actually be able to address certain questions that science by itself is not equipped enough for. But, how is one to envisage such an analysis in the first place? Perhaps, one can begin by acknowledging the fact that most community-centered events or phenomena, whether virulent or benevolent, have the potential to crystalise into a social institution. This isn’t to assume that one wishes or even imagines a pandemic to get institutionalised. But, certainly, there exist certain institutions that decide what does and does not constitute a pandemic. The right to decide what is an anomaly is generated by a complex interplay of politics and dominion of one kind of knowledge system, often being sanctioned by the larger society. This idea was most articulately invoked in an introductory article to a unique pandemic-themed issue of a reputed peer-reviewed journal, Sociology of Health & Illness. In the article, the authors (Dingwall, Hoffman & Staniland, 2013) raised a crucial point by stating that this knowledge and its related technical know-how is mediated into society by a myriad of pathways and that it even signifies a social process. For example, in this ongoing pandemic, we have been quite at the mercy of the scientific and medical industries, who decided and prescribed precautionary measures for nations around the globe that are needed to be followed in order to contain the ill-effects of the COVID 19. However, the way in which they were incorporated into public policy and the way that knowledge regarding the same was disseminated clearly seems to be lacking in a certain kind of rigour. In a country like India, with such a pluralised society, what the concerned authorities seemed to have forgotten is that culturally different communities of people would react to the repercussions of a pandemic in different manner. While there are people who understand the seriousness of this pandemic and will adhere to the concerned safety rules being prescribed such as physical distancing, wearing of protective attire and masks, use of hand sanitizers among the many, there are many people still who will not or cannot follow such protocol. For example, street dwellers or other socially and economically disadvantaged groups are more susceptible to the ills of such a pandemic, primarily due to a lack of accessible economic and social resources like wealth, education and social status. Naturally, it is also very likely that they are unable to access proper facilities like medical help and rehabilitation to reverse its effects. Intellectual Inequality and its Impact on Society

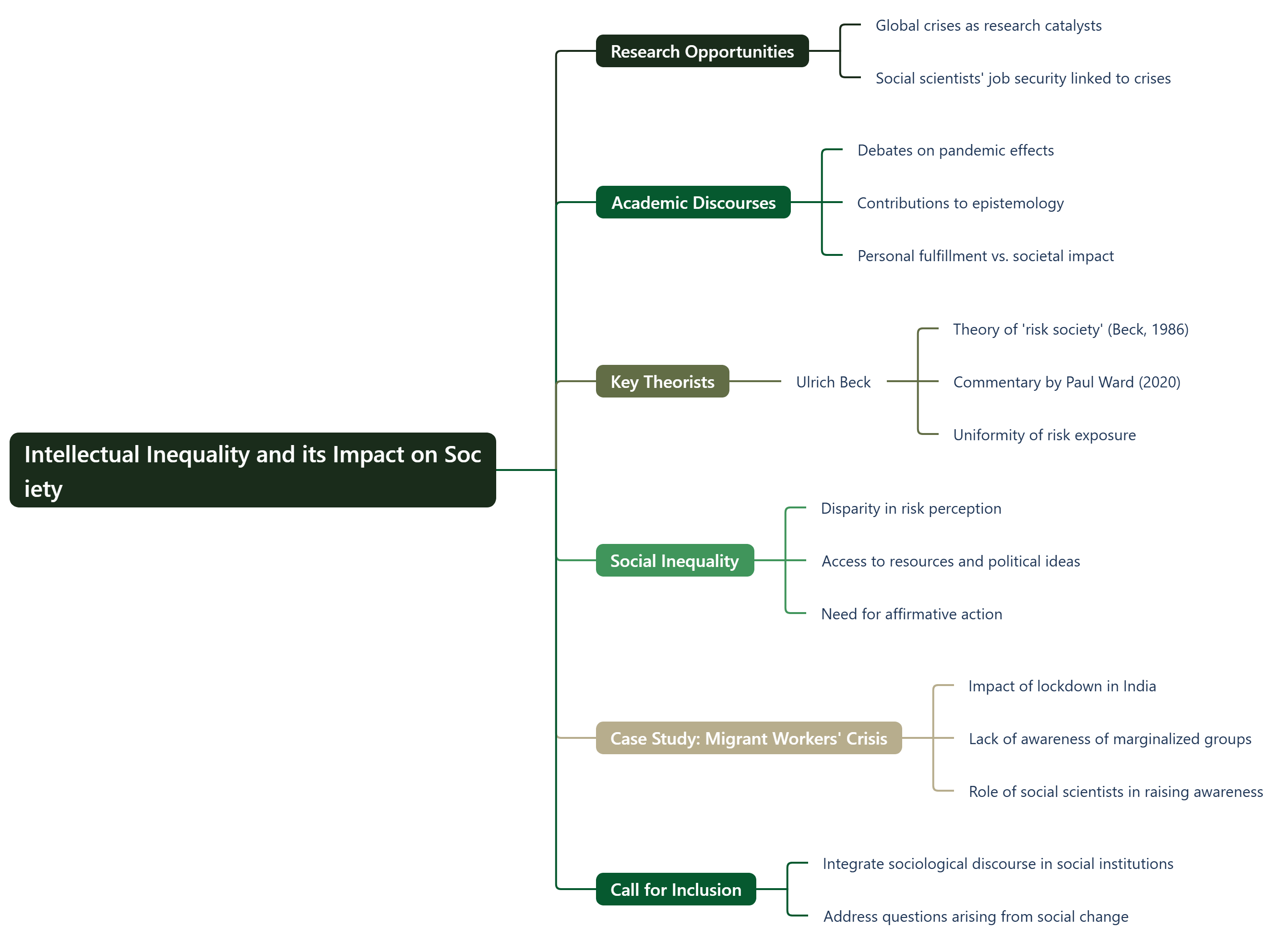

The ongoing, often humorous notion in the past year among social scientists has been that, while the world in beyond doubt, negatively impacted by an event such as this, it opens up an array of research areas for social scientists, which is obviously viewed in a positive light by them. In a way, social scientists would be out of jobs, were it not for war, the dynamics of social institutions, disease and anarchy! In academic spheres, there are plenty of discourses available that debate the nature and effects of a global crisis like that of a pandemic on human societies. Various theorists, analysts and academicians partake in such discourses with a varying range of purposes; from personal academic fulfillment to contribution to epistemology that may eventually affect a positive impact on society. Even in this COVID 19 pandemic, many social theorists have stepped forward for assessing the situation at hand. One of the most popular names that one is reminded of in the context of global crises is of course Ulrich Beck, thanks to his intriguing theory of ‘risk society’. (Beck, 1986) In a very recent commentary by Paul Ward (2020), Beck was in fact, among the many theorists whose ideas were explored in context of the current COVID 19. Going by the lens of risk societies, that is, the likelihood of being unable to contain the negative impacts of scientific advancement in society, the author highlighted how Beck’s theory, at its core assumes that all risks are faced by society in a uniform manner. However, although the author raised the justified question of social inequality and the related susceptibility of some individuals to the ills of risk like COVID, one important idea that seems to be missing in this narrative is the possibility that the general society is yet quite far from identifying something as a ‘risk’ in the society. Once again, the notion that I would like to advocate here is that there is a discernible inequality when it comes to access to not just material resources, but also some political ideas and discourses that can provide both, a stimulating narrative for channeling some kind of affirmative action as well as the ability to proactively work towards avoiding any mistakes in the future. To explain this, the first example that pops in the mind is that of migrant workers’ crisis during the initial months of the lockdown in India. Indeed, the seriousness of a lethal viral fever, coupled with the problems of one of the strictest lockdown norms in the world was briefly felt among the Indian populace, but not many people were sensitized to the extent of disharmony that such a lockdown had brought in a systemically marginalised group such as that of the migrant workers. Somehow, the brunt of this sensitization is to be borne only by social scientists themselves, while other mainstream epistemes continue to ridicule their efforts to bring about communal empathy from the society. An attempt needs to be made to include sociological discourse within the purview of social institutions in order to derive answers for the many questions arising through social change. Working towards the Involvement of Society in a New SociologyAs mentioned previously, the lack of access to discourse beyond academia and social theorisation is certainly preventing society from developing empathy and sensitivity to the problems that accompany an event like that of a pandemic. One of the ways in which this can be achieved is by harmonising the efforts of not only scientists, engineers, medical practitioners and civil authorities, but also using insights that come from the efforts of social theorists, political scientists, social workers and other humanitarian entities. Countries and nation-state authorities need to facilitate an ethnographic inquisition of world health crises in order to ensure that all communities get an equal chance to access resources for self-development and rehabilitation. The ‘Sociology of Pandemics’ needs to work beyond the efforts of social researchers and NGO workers. It is up to the state to ensure that enough resources are allotted to all people without any undue discrimination and one way to ensure this is by using insights from all sections of society. It is long overdue that the politics of knowledge production and dissemination gets diminished. ConclusionThere have been many debates on what the sociology of pandemic looks like or should look like. This article in no way seeks to negate the impact that its predecessors have made, mostly because it is impossible to do so. However, hopefully, with this article, newer conversations can be had regarding the same question. |