Relevance: Sociology

Why in new?

During public health emergencies, like the outbreak of the coronavirus, it’s essential to stay informed. But a lot of that information, when it’s not misleading, can be overwhelming and confusing—down to the very words we use to talk about a crisis.

What’s the difference between quarantine and isolation?

In everyday conversations, people sometimes use quarantine and isolation interchangeably to refer to separating people in various ways due to the spread of a disease. But for doctors, public health officials, and other professionals, there is an important distinction between quarantine and isolation.

What does quarantine mean?

In general, a quarantine is “a strict isolation imposed to prevent the spread of disease.” We know what you might be thinking: so, a quarantine is … just an isolation? Not exactly.

As the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) explains, the practice of a quarantine specifically involves:… the separation of a person or group of people reasonably believed to have been exposed to a communicable disease but not yet symptomatic, from others who have not been so exposed, to prevent the possible spread of the communicable disease.

The takeaway: People are put in quarantine when they are not currently sick, but have been or may have been exposed to a communicable disease. This can help stop the spread of the disease.

Voluntary quarantine (when someone isn’t ordered to go into quarantine but chooses to do so just out of caution) is often called self-quarantine.

Entering English in the early 1600s, this “isolation” sense of quarantine comes from the Italian quarantina, a period of forty days, derived from quaranta, the Italian for “forty.” (The Italian quaranta, if you’re curious, comes from the Latin quadrāgintā, also meaning “forty.”)

What’s so special about 40?

Historically, a quarantine referred to a period—originally of 40 days—imposed upon ships when suspected of carrying an infectious or contagious disease. This practice was done in Venice in the 1300s in an effort to stave off the plague.

What does isolation mean?

In general, isolation is when someone or something is set apart or separated from other persons or things. In medical contexts, isolation specifically means “the complete separation from others of a person suffering from contagious or infectious disease.”

Again, according to the CDC, the practice of isolation entails:

… the separation of a person or group of people known or reasonably believed to be infected with a communicable disease and potentially infectious from those who are not infected to prevent spread of the communicable disease. Isolation for public health purposes may be voluntary or compelled by federal, state, or local public health order.

The takeaway: isolation happens when a person is infected with a communicable disease, and is separated from people who are healthy. This also helps stop the spread of the disease.

Voluntary isolation is sometimes called self-isolation, although everyday people using the latter term may not mean they are actually infected.

First recorded around 1825–35, isolation ultimately comes from the same root as insulation: the Latin insulātus, “made into an island,” based on insula, “island.” Isolated is recorded around 1755–65.

What is social distancing?

The COVID-19 outbreak has introduced many people to the term social distancing for the first time. In public health contexts, social distancing generally refers to various measures that reduce close contact (increase distance) between large groups of people (hence social).

According to the CDC, social distancing involves “remaining out of congregate settings, avoiding mass gatherings, and maintaining distance (approximately 6 feet or 2 meters) from others when possible.” And congregate settings include “crowded public places where close contact with others may occur, such as shopping centers, movie theaters, stadiums.”

Social distancing measures often entail canceling big gatherings (such as conferences, classes, and sporting events), restricting mass transit and travel, and working from home.

It’s not to be confused with the concept of social distance in sociology, or “the extent to which individuals or groups are removed from or excluded from participating in one another’s lives.”

As part of their own efforts to social-distance (as many are verbifying social distancing), people may say they are “isolating” or “self-isolating.” Keep in mind that these more casual uses of isolation don’t necessarily mean they are infected, as when the CDC uses isolation!

What is the difference between social distancing and physical distancing?

Some health professionals are increasingly encouraging the use of the term physical distancing as a clearer alternative to social distancing. Physical distancing underscores the importance of keeping physical distance between people to help stop the spread of the coronavirus. The term additionally makes clear that people should still spend time with friends and family using digital technology and social media when they are physically separated.

In the sociology, social distance includes:

Affective social distance: One widespread view of social distance is affectivity. Social distance is associated with affective distance, i.e. how much sympathy the members of a group feel for another group. Emory Bogardus, the creator of “Bogardus social distance scale” was typically basing his scale on this subjective-affective conception of social distance: in social distance studies the center of attention is on the feeling reactions of persons toward other persons and toward groups of people.

Normative social distance: A second approach views social distance as a normative category. Normative social distance refers to the widely accepted and often consciously expressed norms about who should be considered as an “insider” and who an “outsider/foreigner”. Such norms, in other words, specify the distinctions between “us” and “them”. Therefore, normative social distance differs from affective social distance, because it conceives social distance is conceived as a non-subjective, structural aspect of social relations.

Examples of this conception can be found in some of the works of sociologists such as Georg Simmel, Emile Durkheim and to some extent Robert Park.

Interactive social distance: Focuses on the frequency and intensity of interactions between two groups, claiming that the more the members of two groups interact, the closer they are socially. This conception is similar to the approaches in sociological network theory, where the frequency of interaction between two parties is used as a measure of the “strength” of the social ties between them.

Cultural and Habitual Distance: Focuses cultural and habitual which is proposed by Bourdieu (1990). This type of distance is influenced by the “capital” people possess.

It is possible to view these different conceptions as “dimensions” of social distance, that do not necessarily overlap. The members of two groups might interact with each other quite frequently, but this does not always mean that they will feel “close” to each other or that normatively they will consider each other as the members of the same group. In other words, interactive, normative and affective dimensions of social distance might not be linearly associated.

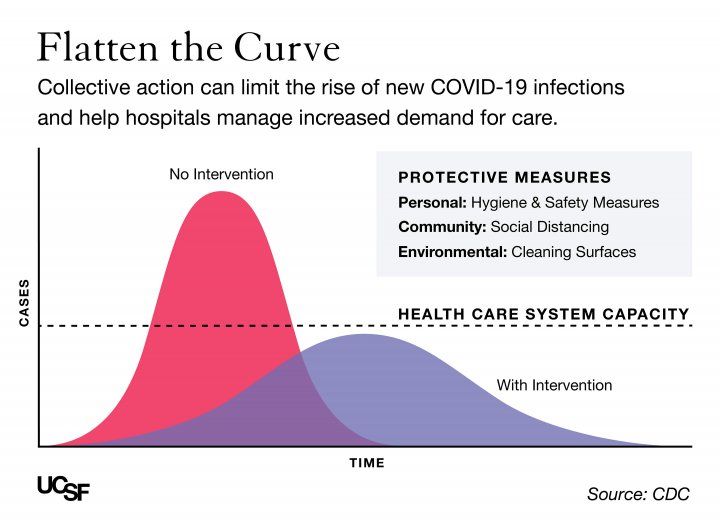

Social distancing is one such action, now in increasingly wide effect. But how does it help, what exactly does it entail, and how do you practice it without sacrificing your physical and mental health?

Why it’s necessary in the context of COVID-19?

Social distancing saves lives by slowing the spread of infection over a longer period of time,

To combat those social ills, we should replace the term “social distancing” with the more precise “physical distancing.” In fact, when we practice physical distancing, we need social connectivity and social responsibility more than ever.

For more such notes, Articles, News & Views Join our Telegram Channel.

Click the link below to see the details about the UPSC –Civils courses offered by Triumph IAS. https://triumphias.com/pages-all-courses.php