Observers have long been ambivalent about regionalism as a principle underlying the organisation of politics. Analysing data from India, this article shows that when regionalist parties win elections, there is an increase in local violence, caused by heightened insecurity among local minority groups. This is found to be especially true for electoral constituencies with significant populations of scheduled tribes who have no mandated political representation.

Many Indian states have ethnic populations that are the minority nationally but the majority locally. This is by design – the States Reorganisation Act of 1956 re-drew state borders to contain local ethnolinguistic majorities. Moreover, in the decades since independence, significant decision-making authority has been devolved to state governments. These factors have together spawned a host of regionalist political movements and political parties across the country, as considerable political power can be attained through narrow appeals to local ethnic majorities.

While regionalist parties offer the possibility of greater national recognition for local ethnic majorities, observers have long been ambivalent about regionalism as a principle underlying the organisation of politics (Brancati 2006, Alonso and Ruiz-Rufino 2007, Wimmer, Cederman and Min 2009, Cederman, Wimmer and Min 2010). Political parties tend to advocate for the interests of their supporters. If regionalist parties exist to advocate for the local ethnic majority, then they – by their very nature – enhance the salience of ethnic and regional identities. Regionalist parties may ultimately facilitate the mobilisation of citizens for civil conflict – wittingly or not.

We believe that much of the ambivalence towards regionalism is rooted in uncertainty about the role that regionalist parties play in political violence within states. In this article, we set out to identify the causal effect of regionalist political parties on political violence in India (Kapoor and Magesan 2020). Specifically, we study how the election of a regionalist party member to the state legislative assembly (as a member of the legislative assembly (MLA)) affects political violence in the constituency of the MLA.

Empirical strategy

There are two main empirical challenges in estimating the effect of a regionalist party representative on local political violence, which our research overcomes. The first challenge relates to defining and identifying regionalist political parties. The second challenge relates to separating the causal effect of regionalist party representation on local political violence from other confounding factors that may influence local political violence, such as history of violence in the region.

Our conceptual definition is as follows: a party is a regionalist party if it makes appeals on issues that disproportionately affect voters in a particular geographical region. Operationalising this definition in a precise way is difficult because it requires taking a stance on what constitutes a regional issue. We address this by requiring a regionalist party to satisfy the following two conditions: (i) Official recognition as a “state party” by the Election Commission of India, and (ii) Electoral support for the party being highly concentrated geographically.

The first condition rules out national parties, independent candidates, and other small parties that run for idiosyncratic reasons. The second condition rules out officially recognised “state” parties that represent voters in multiple states. By our calculations, India has had no less than 80 regionalist parties compete in elections over the last half century.1

To estimate the causal effect of regionalist party representation, we draw on elections data from the Election Commission of India, political violence data from the Uppsala Data Conflict Program (UCDP), and socioeconomic data on tribal persons from the 44th Round of India’s National Sample Survey. The data covers the period from 1989 until 2012. We make specific use of the large number of regionalist parties (and thus, regionalist party candidates), the fact that India’s 28 states regularly elect MLAs,2 and that we observe elections in a total of over 4,000 electoral constituencies spanning several years. These features facilitate a causal interpretation of the relationship between regionalist party representation and local political violence, as we are able to compare violence in constituencies where a regionalist party candidate narrowly defeated or lost to a national party candidate.3 This provides a relatively clean comparison across constituencies, as constituencies where these close elections take place are likely similar in terms of the unobservable characteristics that may influence local political violence.

Main finding: Election of regionalist party candidate increases local political violence

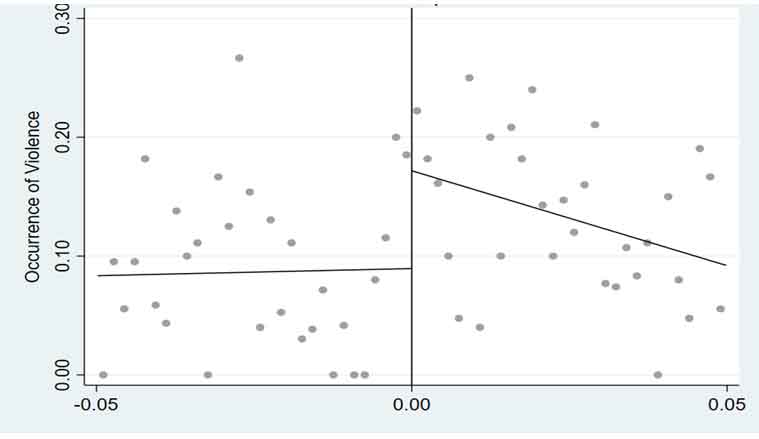

In Figure 1 below, each dot is the average incidence of violence at a particular margin of victory or defeat for a regionalist party (against a national party). If the margin is greater than 0, then the dots measure the average incidence of violence in cases where a regionalist party candidate narrowly won the election. If the margin is less than 0, then the dots measure the average incidence of violence in cases where a regionalist party candidate narrowly lost.

Figure 1. Election of regionalist party candidate increases local political violence

Note: Figure 1 plots the incidence of violence following an election against the difference in vote shares between regionalist and national parties.

Note: Figure 1 plots the incidence of violence following an election against the difference in vote shares between regionalist and national parties.

The figure shows a distinct increase in the incidence of violence when a regionalist party candidate narrowly wins an election.4 Specifically, we show that the election of a regionalist party candidate increases the probability of political violence occurring within the boundaries of their constituency by 7.2 percentage points and the number of events involving political violence by more than 10%.

What explains the main finding?

India has two broad areas with high levels of regionalist party popularity and political violence – the Northeast and the tribal belt.5 Both areas have witnessed significant tensions between the local ethnic majority and scheduled tribes (ST).6 These tensions underlie long-running conflict in Assam as well as an important dimension of the Naxalite7 conflict in Andhra Pradesh and surrounding states.

We show that there is no increase in violence in constituencies where the state assembly seat is reserved for ST populations. The increased violence originates instead in constituencies where the ST population is non-negligible but where the state assembly seat is not reserved for an ST person. In these constituencies, the election of a regionalist party representative increases the occurrence of political violence by over 10 percentage points, and the number of events involving political violence by 18%.8 The estimates are consistent with regional party representatives heightening insecurity specifically in places where ST persons are underrepresented.

The state of Assam provides a useful illustration. In response to local demands for greater autonomy and recognition of the Assamese identity (the ‘Assam Agitation’9), the Centre devolved power to the state in the mid-1980s. Local tribal leaders, who also viewed their people as ‘sons of the soil’ in Assam, anticipated increased marginalisation of tribal people in Assam, as the Assamese identity was given de-facto prominence in local institutions. The late 1980s witnessed an increase in violent conflict between Assamese state forces and tribal insurgent groups that demanded autonomy from the Assamese state. In essence, the conflict between the Indian state forces and Assamese insurgents during the agitation had been replaced by conflict between the newly formed Assamese establishment and tribal insurgents.

We present direct evidence in support of this interpretation. We estimate the causal effect of regionalist party representation on economic outcomes for ST households using the first national survey of ST persons in India (NSS, 44th Round, 1988-89). We show that regional party representation decreases reported wages of ST households,10 their consumption of media (television, radio, and newspapers), and cultural goods (attendance at cinemas or theatres). This evidence implies that regional parties further marginalise already marginalised ST populations.

Conclusion

Altogether our study suggests that representation by regionalist parties increases violence because these parties add to the political and economic insecurity of underrepresented ST populations. Our evidence is consistent, more generally, with local majority representation increasing insecurity for local minorities. It suggests that this insecurity is a cost to decentralising or devolving political power to peripheral regions in a large developing federation.

Notes:

- More details about the validity and reliability of our measure can be found in Kapoor and Magesan (2020).

- State assembly elections to elect MLAs are generally conducted once every five years.

- We use a close elections regression discontinuity design. Regression discontinuity design is an econometric technique used to estimate the effect of an intervention when the potential beneficiaries can be ordered along a cut-off point. The beneficiaries just above the cut-off point are very similar to those just below the cut-off. The outcomes are then compared for units just above and below the cut-off to estimate the causal effect of the intervention.

- This is confirmed by our econometric analysis.

- India’s tribal belt refers to contiguous areas of settlement of tribal people of India.

- Scheduled Tribes are tribes that have received official designation and are recognised as such in the Constitution of India.

- Naxalite is the general designation given to several Maoist-oriented and militant insurgent and separatist groups that have operated intermittently in India since the mid-1960s.

- Events are identified as involving political violence by the UCDP if at least aparty was organised, used armed force, and if at least one person died. The occurrence of political violence equals 1 if such events occurred in the ensuing inter-election years and 0 otherwise. The number of events involving political violence counts these events (0, 1, 2, 3, …) for the ensuing inter-election years.

- The Assam Movement (1979-1985) was a movement in Assam, India, that demanded that the Government of India detect, disenfranchise, and deport non-citizens.

- Most of the respondents are from Assam.

Courtesy : Sacha Kapoor (Erasmus University Rotterdam) , Arvind Magesan (University of Calgary).