Relevance: Prelims/Mains: G.S paper III: Indian Economy: Agriculture

Context

Several states have different levels of capabilities. Some states like Haryana and Punjab are historically in a better position to procure, while others like Bihar have limited capabilities.

Analysis

Farmers’ protests about low harvest prices were a recurrent issue during the harvest period. A record harvest of paddy and other crops was expected during this harvest period. Market arrivals begin from October and end until December across India.

Significant efforts from the Union and state governments are needed to make arrangements for ensuring remunerative prices.

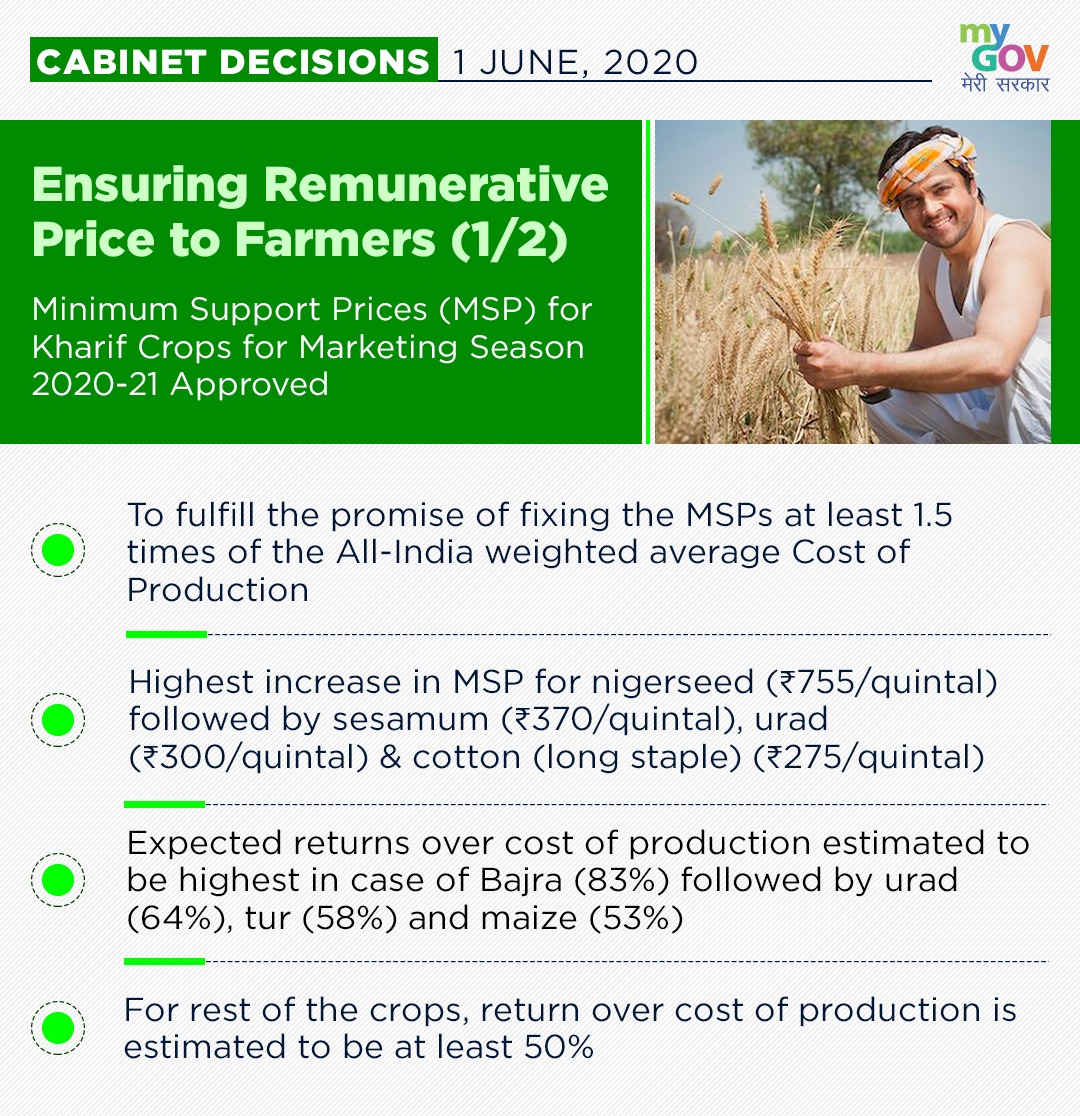

The Union government took the policy decision to guarantee minimum support price (MSP) to cover at least 1.5 times the production cost if prices fall below it. Towards this end, the Centre announces MSP for 25 major agricultural commodities each year in both crop seasons.

Problems in implementation

The bigger challenge is for the announced MSP to be translated to real gain in farmers’ incomes. It is a gigantic task, needs significant budget allocations and support from state governments.

Several states have different levels of capabilities. Some states like Haryana and Punjab are historically in a better position to procure, while others like Bihar, Odisha and other eastern states have limited capabilities to procure.

Farmers in Haryana and Punjab, thus, receive higher prices than farmers in east Indian states for the same crops, including paddy and wheat. There were no proper procurement mechanisms for pulses, oilseeds and other crops — except paddy and wheat — since the Green Revolution.

During the previous harvest season, for example, market price for soybean was 6-13 per cent less than the MSP and for groundnut 20-40 per cent less than the MSP in most of the markets.

This discriminatory policy hugely disincentivised growing these crops, resulting in huge deficits and high-import dependency. India imported 70 per cent edible oils for domestic consumption each year, for example, incurring a Rs 70,000 crore cost to the exchequer.

PM-AASHA

The Centre introduced Pradhan Mantri-Annadata Aay Sanrakshan Abhiyan (PM-AASHA) in 2018 to correct policy bias in procurement operations and ensure farmers growing pulses and oilseeds and actually get the MSPs they were promised for their crops.

The policy also took into account differences in crops, state capabilities, local preferences, feasibilities and gave flexibility to state governments to choose different operational modalities to ensure MSP for each crop.

PM-AASHA has three sub-schemes: Price Support Scheme (PSS), Price Deficiency Payment Scheme (PDPS) and the pilot of Private Procurement and Stockist Scheme (PPSS).

PSS is actual procurement by Union / state government procurement agencies at MSP from the farmers during the harvest period. It may be adopted where there is sizable concentration of production, giving economies of scale to procurement agencies in handling procurement operations.

Under this scheme, the Centre compensates states up to 25 per cent of production for any losses. Although PSS was in existence for more than three decades for paddy and wheat, its implementation for procuring pulses and oilseeds was poor.

Under PM-AASHA, PSS is implemented for procurement of pulses, oilseeds and copra at MSP. Past experience showed PSS implementation was hindered by several factors:

- Lack of awareness about MSPs

- Lack of working capital with procurement agencies

- Arrangement of gunny bags

- Transportation facility

- Delayed payments to farmers

- Logistic arrangements like godowns

- Processing mills in the procuring areas

- Disposal of procured stocks

- Open market operations

- Reimbursement of losses

Under PDPS, farmers are paid the difference between MSP and the modal price of the market without actual procurement. It is the most efficient method as it eliminates all logistic costs related to procurement, storage and offloading. It is advisable to implement PDPS for crops with scattered and thinly distributed production, like oilseeds.

Under PPSS, private players can procure oilseeds at the state-mandated MSP during the notified period in select districts or markets of agricultural produce market committees, for which they would be paid a service charge not exceeding 15 per cent of the notified support price.

States are free to choose among these sub-schemes for oilseeds. The most suitable mechanism for oilseeds, however, is PDPS as it does not require physical procurement by government agencies and depends on market signals and market players for buying at ongoing market prices.

Historically, oilseed prices were mostly determined by free play of domestic and international market participants with almost zero import tariff rates and negligible government intervention by its MSP procurement.

With India importing about 70 per cent of its domestic consumption each year, Indian edible oilseed prices are more aligned with international prices than influenced by domestic market imperfections.

Under this scenario, the price mechanism of oilseeds is determined by free market forces. It is, thus, important for government policy to not intervene in free market forces of oilseeds and price deficiency payment through direct money transfer by using the already existing Jandhan-Aadhar-Mobile (JAM) trinity.

The actual procurement at MSP cannot reach more than 20 per cent of peasantry. The augmented procurement of pulses and oilseeds through PSS and PPSS, thus, cannot be a solution to rising farmers’ incomes. The actual procurement reached only five per cent of market arrivals for pulses and oilseeds in 2019 crop season.

PPSS is a non-starter in many states due to a limit imposed on service charge to be paid by government to private procurement agencies, as 15 per cent is uneconomical in procuring from scattered and thinly distributed oilseeds production areas.

In the long run, thus, the only alternative is PDPS as it does not require physical procurement, avoids logistic and storage expenditure, is free from operational inefficiency, corruption and reaches all farmers.

The PDPS schemes can take advantage of huge procurement, storage and distributional networks of private players in procuring, transportation, storing and disposing oilseeds, coupled with price deficiency payment to farmers using the JAM trinity. This can also reduce the burden on governments, enhancing market efficiency and cost effectiveness.

For more such notes, Articles, News & Views Join our Telegram Channel.

Click the link below to see the details about the UPSC –Civils courses offered by Triumph IAS. https://triumphias.com/pages-all-courses.php