COVID-19 & The Plight of Reverse migration of workers

Relevance: Sociology: Work and economic life: Formal and informal organization of work; Labour and society;Social Change in Modern Society: Agents of social change; Rural and Agrarian Social Structure:Rural and Agrarian transformation in India: Problems of rural labour, bondage, migration.Components of population growth: birth, death, migration. & G.S paper I: Society and social issues & G.S paper II Governance

Context:

- The Home Ministry’s announcement on Sunday evening to seal inter-State and inter-district borders, following the appalling exodus of thousands of workers from the Capital, underscores the lack of prior preparation in implementing the three-week nationwide lockdown.

ANALYSIS

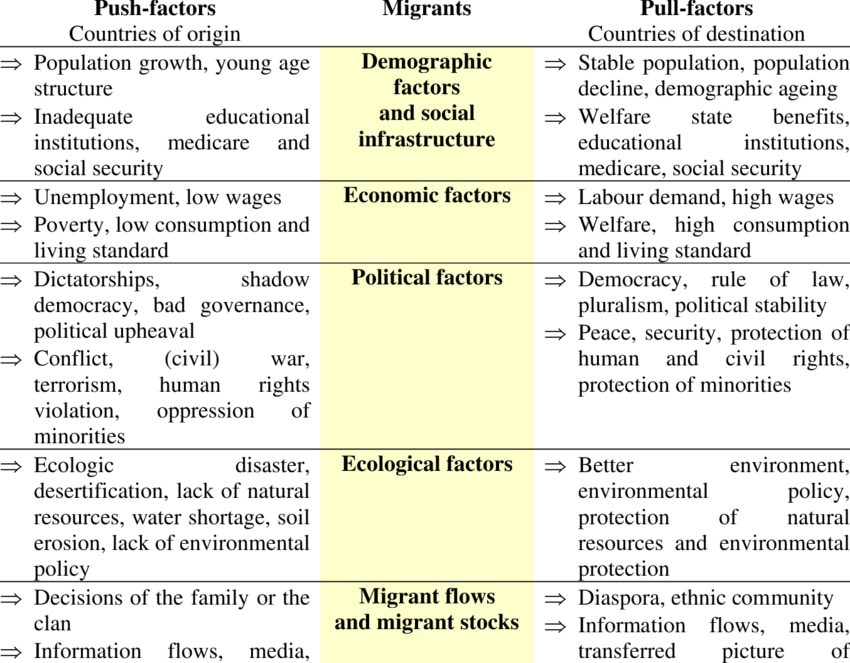

The unfurling human tragedy that has surfaced along with the pandemic in the country has exposed the stark realities of migration and the lack of a social safety net for the poor in the country, with or without COVID in the picture.

Suffering , due to lack of employment, non-sustainable agricultural income, poor marginal labour from the villages move into the cities in search of a better life.

Many of their families are struggling to repay large debts, for which they have to earn, even if it means staying miles apart from their families, visiting them only occasionally.

However, the cost of living in the city coupled with their meagre, often uncertain, income barely leaves anything in their hands for a sudden emergency.

Lack of Documentation & Absence of social security

Lacking identity documents, most workers remain out of the coverage of the Public Distribution Schemes (PDS) in their city of employment.

The MRP of rice, pulses and other staples at the regular shops are too expensive for them to afford, especially in times such as these, when whatever little income they had has dried up too.

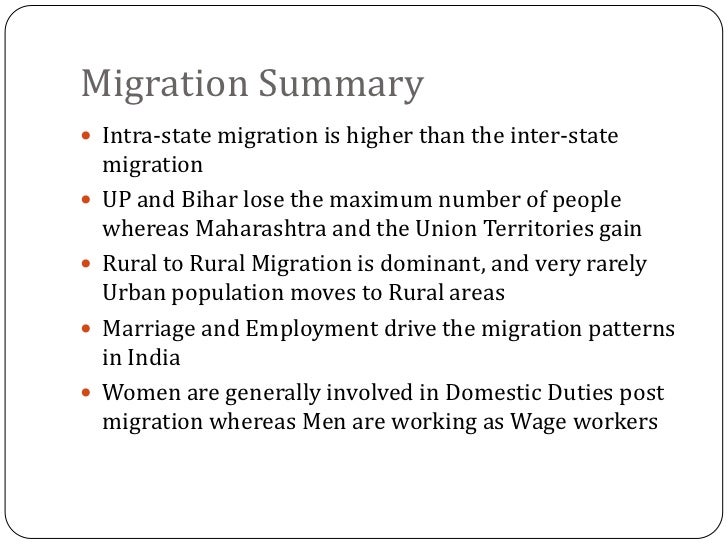

According to Aajeevika Bureau, neither the national Census nor NSSO captures the data of migrant labourers across the country. “Although, independent academic and interdisciplinary data have shown that 139 million of the population are ‘migrating workers’.

While most local economies would crumble without the presence of these interstate migrant workers, there are hardly any institutional bodies that look into the litany of problems they face.

In most cases the migrant labourers are unaware of the Interstate Migrant Labour Act 1979. Their domicile state would have a district authority who should have the documentation that can be shared with the destination state – where people go to work.

Social workers have on earlier occasions raised the need for states to institute migrant workers welfare boards, with a corpus fund for the welfare of this vulnerable section; these boards could strengthen interstate coordination and centres at both source and destination locations that would make it easy for workers to access government schemes..

Workers followed by Discrimination and ostracization

What the COVID-19 migration crisis has also brought under the spotlight is the rampant social discrimination based on caste and class that such workers face on a regular basis.

In few places, a group of returning workers, with kids among them, were sprayed with disinfectant containing a solution of bleach!

Moreover, a few who reached their villages faced hostility even from their neighbourhood over the concern that they had carried the coronavirus from the cities and would now infect the villages.

There are a lot of cases, where we came to know that the migrant labourers were stigmatised due to certain prejudices. These are the places, where the local government is unable to reach with communication or clarity of COVID-19 related information.

Subsequent to the matter being reported in the media, the MHA issued an advisory to all States/UTs to make adequate arrangements for migrant workers to facilitate Social Distancing for COVID-19.

This includes directions to various agencies, including NGOs, to provide free food grains, shelter with basic amenities like clean drinking water, sanitation through the public distribution system.

But despite the reactive measures that have been taken now, the struggle of many continue unabated, creating ample reason for the nation to introspect on how the system treats workers in the informal economy. In the end, it is not just about COVID-19 alone.

Measures need to be taken:

- Now, the workers who have already left Delhi for their homes in neighbouring States will be quarantined for 14 days in their respective State.

• It is inexplicable that the Centre did not foresee the current exodus, triggered by panic and desperation, of Delhi’s informal workforce when it made its surprise decision on March 24.

• This has, in effect, led to a massive dilution of its lockdown measure to contain the virulent coronavirus.

• Steps such as providing for basic needs and ensuring that landlords do not evict tenants for at least a month could have been decided upon before the March 24 announcement.

• The chaos and angst could have been minimised, with the State administrations getting some time to put necessary welfare and law and order systems in place.

• It is hoped that the remaining period of the lockdown will not impose a disproportionate burden on the weaker sections of society.

• Ameliorative measures announced under the Prime Minister’s Garib Kalyan Yojana must be bolstered if necessary.

Delaying in implementation occur problem:

- However, this lapse in implementation also underscores a larger problem: of the informal, migrant workforce not being effectively covered under any welfare or other forms of State protection.

• The Inter State Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1979, spells out the rights of unorganised sectors and the duties of contractors and the State.

• The more recent Unorganised Workers’ Social Security Act, 2008, an outcome of the report prepared by National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector, is by all accounts a watered-down piece of legislation which has not been seriously implemented.

• These laws must be strengthened.

• An important reform measure that brooks no delay is the implementation of the ‘one nation one ration card’ scheme, which could arguably have contained this fear of the future as well as the sudden descent to hunger.

• According to the Economic Survey 2016-17: “The first-ever estimates of internal work-related migration using railways data for the period 2011-2016 indicate an annual average flow of close to 9 million people between the states.” This population falls between the cracks of schemes announced by the Centre and the States.

Way ahead:

- The exodus from Mumbai, Pune, Ahmedabad, Valsad and Jamnagar seems to have subsided.

• However, this “urban avalanche” simultaneously reveals the scale of poverty and fragility of the lives of urban poor.

• Visuals of jeans-clad men with their backpacks walking on the highways may not correspond to the stereotypes about the poor.

• They underscore the desperate need for India’s planners to understand that the poverty line can no longer be defined just in terms of food energy intake or asset possession.

For more such notes, Articles, News & Views Join our Telegram Channel.

Click the link below to see the details about the UPSC –Civils courses offered by Triumph IAS. https://triumphias.com/pages-all-courses.php