Relevance: Sociology: Patriarchy, entitlements and sexual division of labour. Violence against women & G.S paper I: Society and social issues: Women Issues

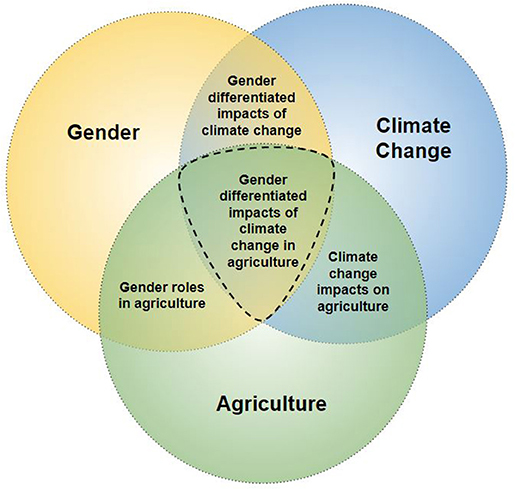

Climate governance policy remains strikingly ignorant of the sociocultural context that it is embedded in, and is thus unable to account for the gender and caste inequalities that are dominant in today’s patriarchal institutions.

According to the World Water Development Report 2020, the devastating impacts of climate change will disproportionately affect the world’s poor, which as of 2017, includes 800 million people (nearly 78% of the world’s poor) who are chronically hungry, and two billion people who suffer from micronutrient deficiencies. A majority of these are situated in rural areas and rely heavily on the primary sector for their livelihoods. This not only puts them at risk individually, but also has dire consequence for the family unit as a whole.

Within the family unit itself, the report predicts that the magnitude of impact on women and girls will be significantly higher and much worse. This largely stems from the prevailing gender inequalities in the world today, and in all likelihood will further add to them, if not accounted for in current policies.

For instance, not only are women and children reported to be 14 times more likely to die than men during disasters, about 80% of the people displaced by climate change are women. This statistic gets exacerbated when one accounts for the fact that current systems still do not allow for women to gain easy access to alternative livelihoods, or even for them to just be mobile in nature.

This stark reality was witnessed during the 2010 Pakistan floods. Moreover, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature has also found that increased environment stress and resource scarcity leads to increase in gender-based violence, which includes domestic abuse, sexual assault, rape, forced prostitution, forced marriages and even a higher incidence of human trafficking in naturally distressed regions.

Despite these statistics, though, climate governance policy remains strikingly ignorant of the wealth and social inequity that surrounds it. This is largely to do with the flawed individualist perception that modern institutions provide equal access to resources, which by virtue of their modernity have been able to successfully invisibilise the discriminatory nature of their institution.

Resources are much more than material assets, they have social, symbolic and relational meanings, and these are gendered.

Need for Including Gender in Climate Governance

Commenting on the Indian National Action Plan on Climate Change and its observation that impacts of climate change would prove particularly severe for women, it is not enough for research and policy to be framed in terms of climate change impact alone.

Since climate change aggravates pre-existing socio-economic vulnerabilities and risk, which the poor and the marginalised confront daily, policy with respect to climate governance must incorporate gendered realities.

The authors note that such an inclusive policy perspective would be important not only keeping in mind the changing relationships between men and women, but also how the identities paradigm plays out in terms of enabling or restricting access to resources and services.

This is pivotal, given that access and control of certain resources to better manage climatic and livelihood uncertainties would require different kinds of solutions for men and women across different social groups.

Moreover, climate variability and environmental change are closely related to already existing issues of women’s personhood and agency, the precariousness of their livelihoods, violence, and bodily integrity.

For instance, they take the example of climate information. The avenue of climate information and communication is integral to give impetus to adaptation and coping strategies for women in rural areas. With this in mind, constructing methodologies to efficiently relay such information would need a gendered approach.

In their paper on climate communication, based on fieldwork in Tamil Nadu, R Rengalakshmi, Manjula M and M Devaraj, point to the fallacies of ignoring gendered needs and understandings in communicating climate information. The types of information needs to vary in response to the particular crops or livestock maintained by women and men, the seasonality of operations and labour requirements, local knowledge, language and idiom, and the avenues for accessing information. They find two-way communication systems delivered through local intermediaries with established relations of trust to be the most effective in communicating climate information to women farmers and smallholders.

Climate Information, Coping Strategies and Patriarchal Knowledge Systems

The essentiality of climate information and its use in adaptation strategies is further explored by R Rengalakshmi, Manjula M and M Devaraj.

The current inequality in access to, and the use of, climate information by women producers becomes significant in a context where 79% of rural women are engaged in agriculture as against 63% of men in India (as per 2011 NSSO data).

This is due to current changes in employment patterns where there’s been a rapid decline in men’s contribution to subsistence and family farming.

This shift of males to non-farm wage employment in urban and peri-urban regions can be seen in the rural areas of Maharashtra, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, and Kerala.

Such changes in the agrarian systems in rural India has pushed women to the front, and made their role in agriculture management more dominant. However, these changes have made tangible their discriminatory access to knowledge production systems.

The social construction of traditional knowledge systems is mirrored by modern ones, restricting their ability to use information and knowledge that would assist them in farming with changing climatic conditions, adapting to new processes of farming given the rate of climate change, or even just more sustainable practices.

This hindered ability to take timely actions for their labour exacerbates their vulnerability to climate change and even distorts the effectiveness of existing climate risk management strategies. Eventually, the authors emphasise, current climate policy seems ignorant of just how socially and culturally embedded knowledge truly is.

Through its refusal to acknowledge such a simple truth, it invariably puts women at much greater risk to the dangers of climate change.

Women’s participation in farm-level decision-making is limited to contribution of labour and execution of agronomic practices like sowing, weeding, and harvesting, based on their traditional roles and experiences. Though women are doing more than 80% of the agricultural work, they seem to lack the confidence to take decisions in the absence of both necessary information and access to inputs from markets. This situation makes women mere contributors of physical labour in crop cultivation. Women’s access to formal agriculture extension services and information relevant to agricultural operations were also inadequate due to their limited institutional linkages and informal networks at the village level. Ultimately, they end up depending on men in the household for any new information and knowledge.

Migration, Climate Refugees and Social Realities of Diaras

Looking further into the aspect of migration, Asish Kumar Ghosh, Sukanya Banerjee, and Farha Naa investigate the cyclone Aila in 2009 in the Indian Bengal Delta and destruction of life and property that followed.

The authors observe that in the wake of cyclone Aila in 2009, approximately half of the men from the most affected blocks of the Indian sundarbans (which is extremely vulnerable to climate change) ended up migrating to other parts of the country in search of alternative livelihoods. However, women were left behind to shoulder the sole burden of running the household and dealing with the aftermath of the cyclone. According to the Government of West Bengal and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), there were approximately 9,20,000 houses that were damaged and 70 lives were claimed.

The destruction to livelihood included cutivable fields being affected by saltwater intrusion. This had a particular impact on farmers who suffered the worst as the cyclone occurred during the harvest season. Cumulatively, since it was women doing 70% of the farm work, the after effects of the cyclone were especially brutal to them.

Not only were they left alone to deal with the broken homes, they were also rendered helpless where livelihood and food security was concerned. Moreover, the intrusion of saltwater in freshwater tube wells rendered them impossible to be used for diluting dry baby food.

The women were also unable to look for alternative livelihoods due to the gender restrictions that employment comes along with. This further led to wage discrimiation, sexual exploitation and harassment in the workplace. As per reports, several of these women from the Indian Sundarbans ended up increasingly migrating to the red-light district of Kolkata due to the climate change-induced distress.

According to Samarajit Jana, an epidemiologist who set up a collective that fights for the rights of sex workers, the number of women who moved to Kolkata’s red-light district increased by 20% to 25% in the aftermath of cyclone Aila. Many of these sex workers identified themselves as bhasha (environmental refugees). Women struggle to get even basic necessities such as sanitary napkins and baby food in the aftermath of natural disasters. They are often bereft of a safe place to live and end up being susceptible to sexual violence. Thus, they have no choice but to migrate to slums in cities, where it is difficult to get work and live in derogatory conditions without any recognition of their rights. Women who are forced to enter into prostitution in order to look after their family and children face social ostracism and the threat of sexual exploitation at the hands of their clients, and fall prey to sexually transmitted diseases like HIV/AIDS.

This immobility of women and their treatment by respective family members in times of disasters is corroborated by Pranita B Udas, Anjal Prakash and Chanda G Goodrich.

They look at “diara” villages which, in the local parlance of Bihar, means a village located inside the embankments of the floodplains of the River Gandak in Bihar, and consequently refers to those living in abject poverty in regions vulnerable to frequent flooding as well as droughts.

Those in these villages either have too much water, or too little, depending upon the climatic context. These vulnerabilities, the authors write, are extremely gendered in nature and peak during times of flood when women, children and the elderly are forced to move due to their special needs and the roles of women as caretakers of the household. Their already existent exclusion from the decision-making process is exacerbated and makes their ability to cope or adapt to changes worse off.

Moreover, in times of disasters, it is the elderlies who are left behind while the household migrates, or the women and the children are made to stay behind. This behaviour has added to the perceptions of the locals about who can survive in times like these and who cannot, and has serious implications for how females and their births are viewed by the village (that is, the perception that having more daughters makes one more vulnerable to floods).

Which household is the most vulnerable during a flood?” we asked people living in diaras. The answer revealed the gender biases in this society. “Households with more daughters are the most vulnerable.” And, why were they the most vulnerable? The response was that such households have limited social and financial capital to respond to floods. Social and financial capital is crucial to cope with stressors.

Coping with Droughts through Invisibilised Labour and Food Insecurity

In their study of household data collected from different drought-affected areas in Odisha, Basanta Sahu further investigates the vulnerabilities faced by women in times of climate crises. Sahu explains that in times of conflict, the household, as a decision-making unit, undertakes various arrangements to manage resource use and basic entitlements.

In these times, the labour of women and its use is seen as crucial for the survival and security of the household. As seen in previous articles as well, Sahu observes that such labour comes to the fore when men migrate to other parts of the country in search of alternative livelihoods.

However, what remains as a constant feature of their lives, is the inadequate and unequal access of women to resources, and their use. In drought-ridden regions, the existing food and water system, undergoes further inequalities to fit into the prevalent gender relations.

Hence, one of the coping strategies that Sahu discusses from the study is the strategy of decreasing the number of family members in stressful times when availability of food is inadequate and unstable.

Here, some family members are sent elsewhere, for instance, children are sent to neighbour’s houses, whereas some are abandoned. The victims of this strategy are usually the non-working women or the elderly. Moreover, intra-household food consumption is the first to disproportionately and adversely affect women.

In response to the question “who faced a bigger drop in food consumption within the household”—although almost all people were affected to some extent, it was more in tribal pockets and among women and elders. All female members of the family were the first to adjust to food consumption and other shortfalls, followed by elders in the family. Many adult women and men experienced an overall decline in food consumption, and about two-thirds of them reported a higher degree of decline.

The Caste Question

Along with gender, caste is also an often ignored variable in climate governance policies, such as access to water. This becomes integral in drafting policies as caste is a crucial determinant of who has access to water and how.

Concerns relating to caste and gender equity have, unfortunately, remained limited to older forms of oppressions faced at community levels, and is not factored in when examining modern institutions, so to say.

in water management systems wherein traditional inequalities have amplified and directed different social groups’ ability to use water. This is particularly pertinent when examining how groups such as the Dalit are kept from water resources due to stereotypical views about purity and untouchability.

The age-old social hierarchy in Hindu society has historically positioned dalits as eternally polluted, feared to pollute sacred water sources (Joshi and Fawcett 2006). The fresh water underground springs (naulas) of these mountain villages are not accessible to the dalits. In these mountain villages and elsewhere, dalits have historically lived in hamlets distanced from the main village and the primary water sources, which were also areas where the main village temples where situated. “Good dalits” are those who keep away from these “sacred” areas. These sites are also forbidden to caste Hindu1 menstruating women until they are purified on the fifth or the seventh day. When the water level suddenly drops or sources dry up, it is rumoured that the water was polluted by menstruating caste Hindu women and purification ceremonies are performed to absolve the pollution. To blame the dalits would justify their access.

For more such notes, Articles, News & Views Join our Telegram Channel.

Click the link below to see the details about the UPSC –Civils courses offered by Triumph IAS. https://triumphias.com/pages-all-courses.php