The basic economic model of labour supply predicts that when an adult receives an unexpected cash windfall they should work less and earn less. This underlies concerns that cash transfers will undermine work ethics and make recipients lazy. In this post, Baird et al. discuss how missing markets, price effects, and dynamic and general equilibrium effects can make this intuition misleading in low- and middle-income countries.

There is growing interest in the promise of cash transfers in the form of government transfers, humanitarian donations, and person-to-person remittances to improve outcomes for poor people around the world (for example, Blattman and Niehaus 2014, Overseas Development Institute (ODI), 2015). However, many policymakers and indeed, much of the general public, are concerned that simply giving cash to people may reduce their desire to work (Banerjee et al. 2017).

This concern is supported by classical economic theory. The standard economic model of labour supply taught in introductory economics classes (‘Econ 101’) has a very clear prediction of what we should expect when an individual suddenly receives an unexpected cash windfall: individuals should work less and earn less. In these models, individuals decide how much to work by trading off the gain from working more hours (more income) against the cost (less leisure). Since leisure is usually regarded as a normal good, an increase in non-work income should then cause an individual to demand more leisure (for example, Becker 1965), and therefore work less. Indeed, Keynes (1930) infamously predicted that because people would be so much richer in the future, his grandchildren would only work 15 hours per week.

Life is more complicated than ‘get more money, buy more leisure’

In a recent paper (Baird et al. 2018), we re-examine the literature on cash transfers and set out a framework for understanding the different channels through which adult labour supply responds to the receipt of cash transfers. These can be broadly grouped as arising from missing markets, price effects from behavioural conditions attached to transfers, and dynamic and general equilibrium effects.

Missing markets

Credit constraints and missing insurance markets can cause four other channels to operate:

- A health productivity effect, where transfers allow workers to become better nourished and start working more.

- A self-employment liquidity effect, where transfers enable poor people to start or expand businesses.

- An insurance effect, where access to a safety net of transfers may cause recipients to undertake risky activities with high potential rewards (for example, starting a business or migrating to a better job).

- An investment in labour search effect, where transfers allow workers to search longer and more intensively, in order to find a higher paying job.

Price effects from behavioural conditions

In practice, cash is often given with conditions attached to it, which can change the labour/leisure trade-off in the following three ways:

- Some cash may be given conditional on it being used to start a business or for job search, or conversely, working too much may disqualify people from future transfers.

- Other transfers may be conditioned on activities that change time availability, such as freeing up parental time when kids go to school.

- Receiving cash transfers as a child can increase education, so that as an adult, the ability to find work and returns to work increase.

Dynamic and general equilibrium effects

The standard model considers an individual making a one-period labour supply choice, which does not affect their future ability to work nor is it affected by decisions others are making. Neither assumption may hold. There may be a human capital depreciation/scarring effect where time out of the workforce can cause workers to lose skills and make it harder to find jobs in the future, so that workers do not stop working when given temporary transfers. General equilibrium effects can arise from both wage rates and the value of leisure changing when others in your community also receive cash.

What does this mean in practice for different types of transfers?

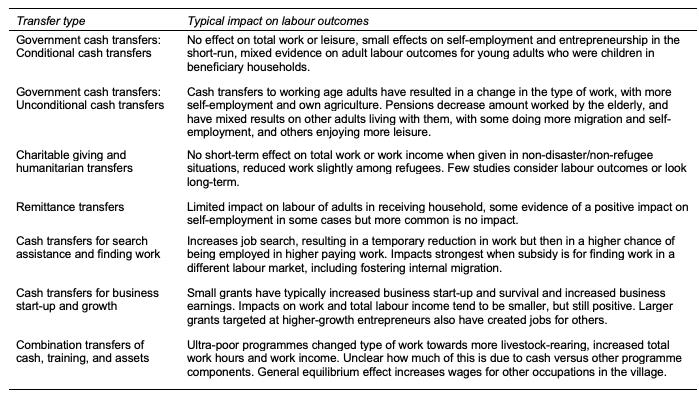

Some of these channels operate to increase the likelihood that adults are employed and the amount they earn from work, counteracting the trade-off with leisure. Others can reinforce the tendency of cash transfers to reduce work. The net effect depends on the type of cash transfer being considered, and the conditions facing those receiving cash. Table 1 summarises our take on the typical impacts of different types of cash transfers.

Table 1. Summary of adult labour impacts of different types of cash transfers

Future research

As cash transfers continue to proliferate in developing countries, the presumption that they will undermine work effort and have less impact than anticipated through a resulting reduction in labour income seems largely unfounded. But the impacts are likely to be different when transfers are dependable and permanent rather than temporary and/or surprises, when the eligibility criteria are known in advance to recipients compared to programmes being unannounced, and when targeted at different types of people. There is thus an active role for future research to attempt to measure and unpack the different channels we describe here in order to better understand these programmes.

Courtesy : Sarah Baird (George Washington University) , David McKenzie (World Bank) , Berk Özler (World Bank).