Relevance: Prelims/Mains: G.S paper III: Environment

Why in news?

Both chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, pose serious chronic threat to the aquatic environment.

Researchers across the globe are testing antiviral drugs as a potential cure for the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Some countries have recommended their frontline workers to consume some of these drugs as preventive medication.

Frontline healthcare workers and slum dwellers were asked to take hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), an anti-malarial drug, as they were at higher risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 virus.

India is the largest producer of the drug and the United States receives 47 per cent of its supply from India alone. After a series of bans and lifts, India finally went ahead with supplying the drug to the US, Israel, Brazil and SAARC countries, among other countries.

India is all set to make use of this opportunity by manufacturing more, also as a possible move to put some brakes on the Chinese pharma industry dominance.

But, how safe are antiviral drugs for the environment?

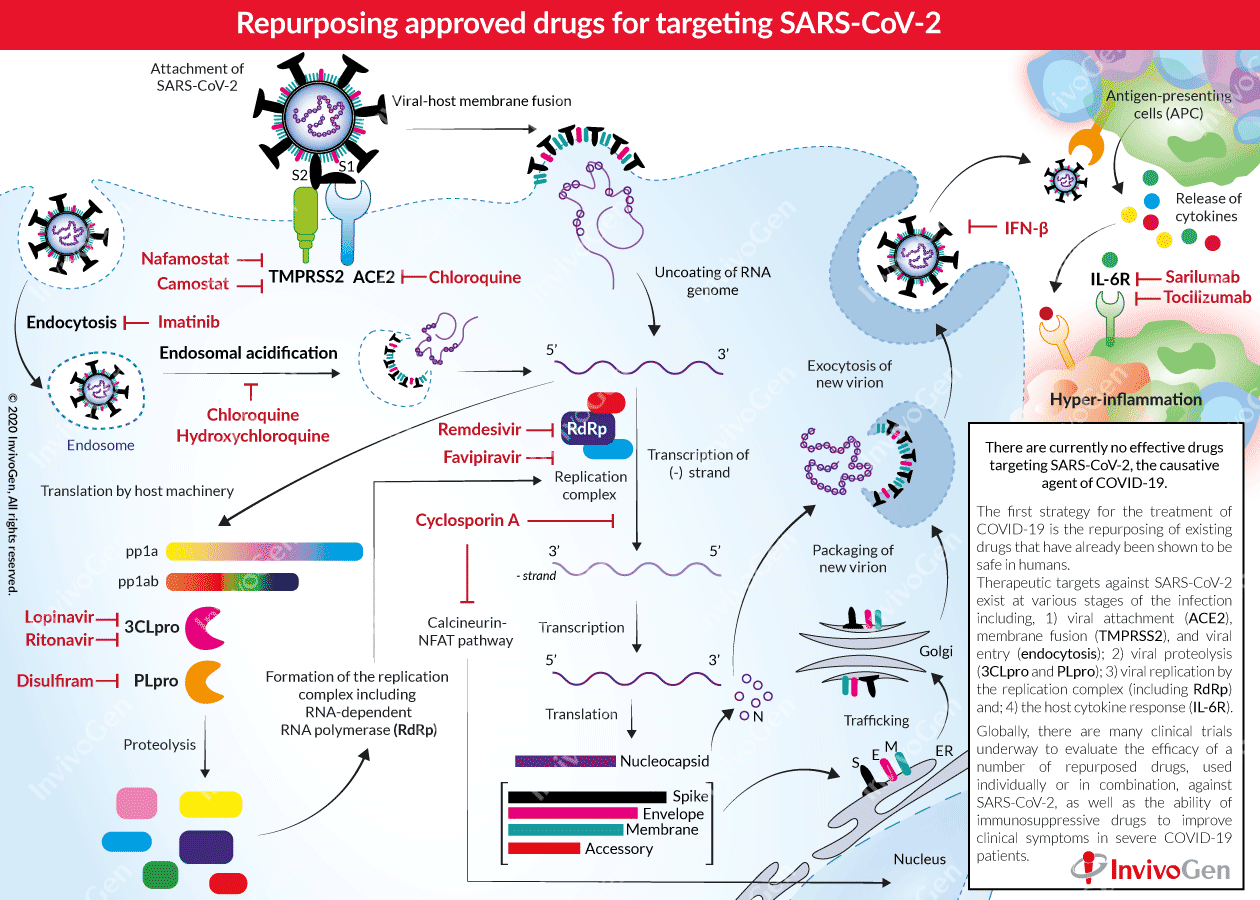

A review article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association collated the therapeutic studies on SARS-CoV-2 and found that remdesivir —an antiviral drug developed to treat Ebola — could be potent against SARS-CoV-2.

This drug is yet to receive approval of the US Food and Drugs Administration (FDA). In the meantime, randomised trials are underway.

Several other antiviral drugs under trial include chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, and ritonavir, favipiravir, ribavirin, oseltamivir, and umifenovir.

These are reported to have several toxic effect on human beings, most commonly causing abdominal cramps, anorexia, diharrhea, nausea, vomiting, gastrointestinal intolerance, reduction in neutrophil count and majorly cardiovascular effects.

The other adverse effects include:

- Hematologic effects

- Hypoglycemia

- Retinal toxicity and central nervous system effects

- Pancreatitis, allergic reaction

- Kidney injury

The drugs are prescribed alone or in combination depending upon the scale of the infection. The dosage can be as high as 500 mg, like in the case for chloroquine phosphate, which has to be administered every 12-24 hrs for 10 consecutive days.

Upon administration, such drugs undergo series of biotransformation and are excreted both in conjugated and de-conjugated form through faecal and urine waste.

The rate of excretion can be as high as 90 per cent for some antiviral drugs.

At the wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), these compounds undergo a series of treatment processes. Due to lack of adequate treatment, however, these drugs enter into the aquatic environment.

Alternate routes through which they may enter into the environment include discharge of untreated wastewater from pharmaceutical industries, hospital wastes, disposal of expired drugs and non-point contamination. This can pose a considerable health risk in countries with poor sanitation facilities.

In another study, scientists detected SARS-CoV-2 viral genome in untreated wastewater. Hence, prolonged exposure of the viral genome to specific antiviral drugs and further development of antiviral resistance cannot be ignored.

Although antiviral drugs are attenuated via photolysis, hydrolysis, sorption, and biodegradation in the aquatic environment, some are reported to be persistent in the aquatic environment with a half-life of more than a year. These drugs are resistant to degradation and are commonly lipophilic (that is, they have an affinity for fats or lipids) in nature.

Researchers studied the eco-toxic effect of antiviral drugs on several aquatic organisms, including crustaceans, fish and algae.

Both chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine posed serious chronic threat to the aquatic environment. Both these drugs belong to a group of quinolone derivatives, which are recalcitrant, persistent, toxic, carcinogenic and teratogenic in nature.

Half-maximal effective concentration (EC50), at which chloroquine can induce a response in Daphnia magna, is 12 micrometre (µM).

Another hydrophobic antiviral Ritonavir, which has been reported to be removed only up to only 25 per cent in a conventional wastewater treatment plant, has an extremely low predicted no-effect concentration (PNEC) of 28 nanogram/litre (ng/L).

PNEC is the concentration of a chemical which marks the limit below which no adverse effects of exposure in an ecosystem are measured.

This means that if the concentration of this drug in aquatic environment exceeds 28 ng/L, it can cause severe adverse effects in certain aquatic organisms such as green algae.

Yet another antiviral drug, Favipiravir, which exhibits low sorption tendency, is highly resistant to biotransformation.

Sorption tendency is a physical or chemical process by which one substance becomes attached to another through absorption or adsorption.

Favipiravir is known to produce a teratogenic effect. While ecotoxicity data for this drug is not well-documented.

Ribavirin, which is the most frequently used nucleoside agents in China, has a PNEC for green algae or blue-green algae less than 100 ng/L. Oseltamivir was detected in the finished water from a drinking water treatment plant in Japan during H5N1 (haemagglutinin type 5–neuraminidase type 1) influenza viruses.

For oseltamivir and oseltamivir carboxylate, the no-observed effect concentrations in algae, daphnia and fish are more than 1 mg/L. While remdesivir has shown more potential among drugs considered for SARS-CoV-2 treatment, enough ecotoxicity studies have not been carried out for this drug.

Environmental safety of antiviral drugs is of significant importance, especially during this pandemic.

Remarkably high concentrations of these drugs are expected in various environmental compartments, including surface water, groundwater and soil matrices, as a result of their increased consumption.

For more such notes, Articles, News & Views Join our Telegram Channel.

Click the link below to see the details about the UPSC –Civils courses offered by Triumph IAS. https://triumphias.com/pages-all-courses.php