Does political reservation undermine or promote development, and for whom? This article presents an analysis of India’s ‘Scheduled Areas’, which reserve political office for the historically disadvantaged Scheduled Tribes. Focusing on the effects on MNREGA, it shows that reservation delivers no worse outcomes overall. There are large gains for targeted minorities, which come at the cost of the relatively privileged rather than other minorities.

Political affirmative action in India, or reservation, has long invited controversy, mobilising some who wish to expand it to new jurisdictions and additional social groups, those who fear its dilution, and others who vociferously oppose it. Political parties have taken sides, and recently the Supreme Court of India weighed in on the obligations of states to implement affirmative action provisions enshrined in the Indian Constitution. How should we evaluate this hotly debated and politically divisive policy?

One way is to engage critically with the claims of its most vocal opponents. Those who are against reservations typically make two central arguments about how development will suffer. First, reservation will hurt overall development outcomes by empowering people who are less competent than the ‘higher merit’ individuals whom they displace. Second, insofar as reservation benefits a targeted minority group, gains will come at the expense of other vulnerable groups with whom they are in competition – not, as is intended, from groups that are comparatively more privileged under the status quo. Evaluating these claims is difficult, as it requires a full accounting not only of the overall effects of reservation, but also how those effects are distributed across groups in society.

Results from our new research (Gulzar et al. 2020), which provides such an accounting, contrast sharply with the expectations of affirmative action sceptics. Indeed, we find that affirmative action can redistribute both political and economic power without hindering development overall, or for non-targeted vulnerable communities.

Political reservation and development

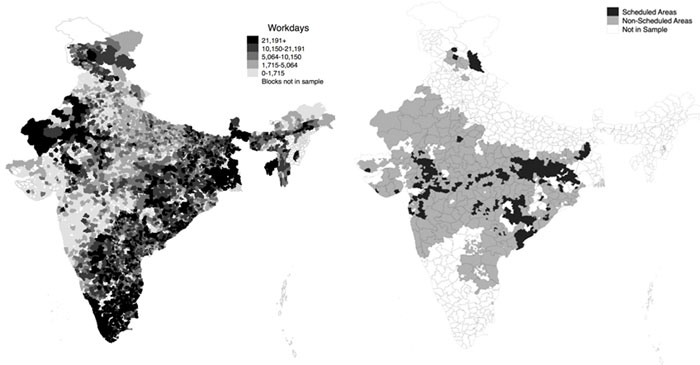

We study ‘Scheduled Areas’ in India, where a political quota reserves half of panchayats (village councils) and all leadership positions for the historically disadvantaged Scheduled Tribes (STs). We compare villages that are located just on one side of the administrative quota border with villages just on the other side – and thus villages that are expected to be as similar as possible, except that some are designated as Scheduled Areas. Our central outcome of interest is the implementation of the world’s largest employment programme, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA)1. Because MNREGA and the Scheduled Areas quota aim to economically and politically empower marginalised groups, studying their interaction provides a particularly powerful test of affirmative action sceptics’ claims: we evaluate if sceptics are correct in positing that restricting representation to STs will be self-defeating, in that it damages the economic prospects of the populations it was designed to empower. MNREGA data also enable us to evaluate the overall outcomes, as well as outcomes for the minority group targeted by the quota (STs), a non-targeted minority group (Scheduled Castes, or SCs), and the comparatively privileged residual category (non-SC/STs). Figure 1 below shows the considerable variation in MNREGA implementation across India as well as our construction of where Scheduled Areas are found in the country.

Figure 1. Variation in 2013 MNREGA workdays across India (left) and Scheduled Areas (right)

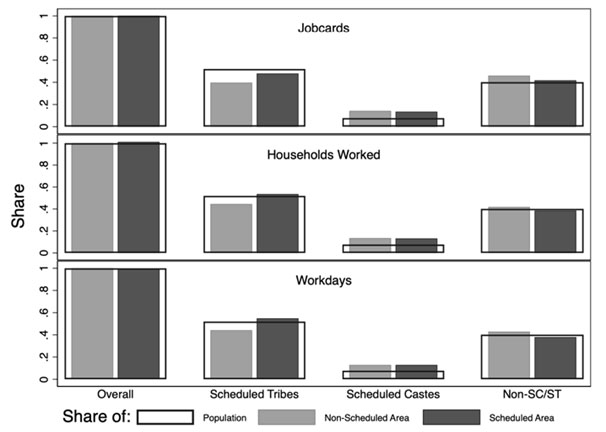

We find that MNREGA delivery improves substantially for the targeted minorities (STs), who receive 24% more MNREGA workdays in Scheduled Areas. Improvement appears to come primarily at the cost of work for non-SC/STs, who receive 11.5% fewer workdays. We find no evidence that the quota causes a change in employment for the non-targeted, historically disadvantaged minorities (SCs). Overall, the results indicate that the delivery of government programmes in Scheduled Areas is no worse than in non-Scheduled Areas. In Figure 2, we show that the share of MNREGA work is more closely aligned with a group’s population shares in Scheduled versus other areas. Taken together, our findings undercut criticisms of affirmative action policies: targeted marginalised groups benefit from quotas, non-targeted marginalised groups fare no worse, and overall development outcomes do not suffer.

Figure 2. Scheduled Areas improve correspondence between MNREGA work and population shares

Broader effects

Are there implications of instituting electoral quotas beyond the effects we observe on MNREGA? To increase our confidence that electoral quotas improved outcomes for poor communities, and to address possible concerns that improved MNREGA implementation might come at the cost of other government programmes, we also consider effects of quotas on two additional outcomes.

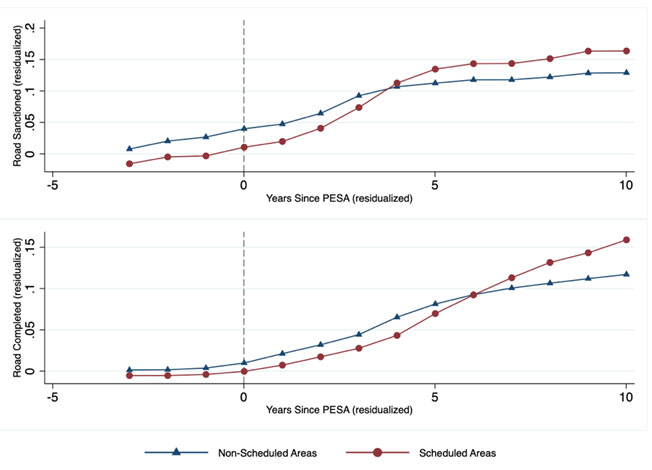

First, we examine impacts on the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY) village roads programme, which was established in 2000 with the aim of connecting rural villages to the all-weather road network. We find that the arrival of reservations under the Panchayat Extension to Scheduled Areas (PESA) Act results in greater road connectivity, and that effects only follow the introduction of elections, indicating that changes are indeed attributable to electoral quotas.

Figure 3. The effect of the introduction of electoral quota (PESA) elections on roads

Second, we consider the effects of Scheduled Areas on the provision of broader public goods that benefit poor communities and find that the average provision of roads, water, communication, and education also improves.

Our analysis of broader effects indicates that effects of quotas are not limited to the MNREGA programme, and points to a greater investment under quota politicians in the welfare of marginalised communities.

What next?

Policymakers often treat economic and political efforts in isolation. We argue that political affirmative action and development programmes may serve as complementary levers to deliver better outcomes for marginalised communities, at no cost to other minorities, or to society overall.

What are the implications of our results on debates surrounding affirmative action? Sceptics routinely argue that open competition in the political sphere brings the best politicians to the fore. However, our results show that quota politicians perform no worse than status-quo politicians. This suggests that status-quo institutions may prevent equally qualified individuals from marginalised communities from running for office and more effectively representing their communities.

An open question that remains concerns the long-term effects of quotas. Our study measures impacts up to 12 years after implementation of the institution, but in the longer-term, fixed political affirmative action, such as the Scheduled Areas quota, could result in similarly unequal political structures to that of today by simply replacing the identity group that is on top. We consider this to be a valuable question worth further exploration.

Note:

- MNREGA guarantees 100 days of wage-employment in a year to a rural household whose adult members are willing to do unskilled manual work at state-level statutory minimum wages.

Courtesy : Saad Gulzar (Stanford University) , Nicholas Haas (Aarhus University) , Ben Pasquale (Independent Researcher).

One comment