The state of Bihar was one of the early starters on Gender Responsive Budgeting in India, having published its first ‘Gender Budget Statement’ in 2008-09. Based on a review of the literature on the state’s policy commitments pertaining to gender budgeting, Dixon and Mishra present their assessment on whether the existing institutional processes and mechanisms within the government operate in harmony to achieve these commitments.

Economic growth unaccompanied by inclusive, equitable and sustainable growth can not only exacerbate future gender equality outcomes, but also prove regressive by pushing progress on gender equality back. In this post, Shrijna Dixon and Yamini Mishra consider the state of Bihar that has witnessed a steady and high economic growth over the last decade and examine how much budgets are being allocated to achieve gender equality and women’s empowerment through Gender Responsive Budgeting (GRB).

Economic growth without inclusive, equitable, and sustainable policies can not only exacerbate gender inequality in the future, but also prove regressive by pushing the progress on gender equality back. In Bihar, a state that has witnessed steady and high economic growth over the last decade, we look at how much budgets are being allocated to achieve gender equality and women’s empowerment (GEWE).

We do so by focussing on Gender Responsive Budgeting, a global framework for mainstreaming gender in a government’s planning and budgeting. Afterall, what a government spends on roughly one-half of its population should be a critical marker of how much it is willing to push the needle against gender inequality. GRB helps governments plan, allocate, programme, and monitor their resources in line with their international and constitutional commitments on GEWE. In fact, through its feminist and intersectional lens, GRB goes beyond women and girls to recognise and thus mitigate/prevent the irreversible negative impact that inequitable budgets can have on the most marginalised and vulnerable sections of society. In our study, we limit our scrutiny to planning and budgeting for the women and girls in Bihar.

The study: Scrutinising Government of Bihar’s budgets for gender equality and women’s empowerment

Since the first documented GRB initiative in Australia in 1984, GRB efforts have been undertaken in over 100 countries globally, with India as one of the leading countries in Asia to have implemented some GRB initiatives. For Bihar, we reviewed the literature on the state’s GRB policy commitments to understand whether the existing GRB architecture (institutional processes and mechanisms) within the government operates in harmony to achieve these commitments.

Governments all over the world use a number of tools to apply GRB, one widely used tool being Gender Budget Statements (GBS), which present budget outlays allocated exclusively for schemes/programmes that address gender needs/discrimination. We scrutinise the GBS for Bihar from 2009-10 to 2019-20. We also draw linear correlations between gender budgets and nominal macro-level fiscal attributes such as the state’s gross domestic product (GDP), state’s share of central taxes, and state taxes.

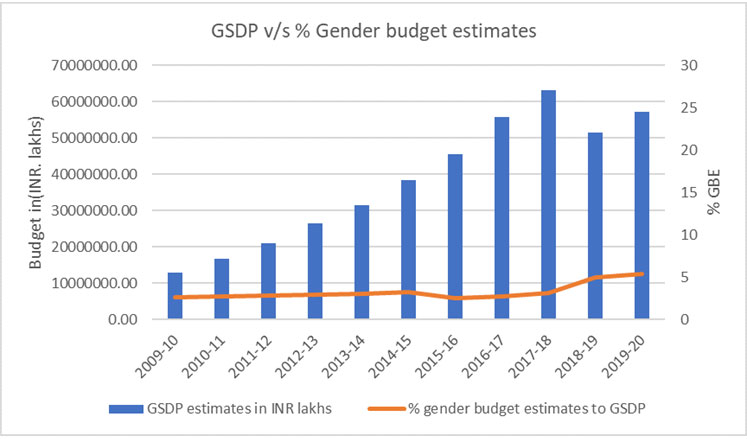

The findings: Policy and budgetary commitments on gender equality should be backed by an effective GRB architecture in Bihar

Bihar registered double-digit growth averaging higher than 10% over the past three years. The state was one of the early starters on GRB in India, having published its first GBS in 2008-09. The total budgetary outlay for GEWE, as reflected in the GBS from 2012-13 to 2017-18, shows an increase by 163%, constituting about 11% of the state’s overall budget. The budgetary outlays in GBS are estimated at about 3% of the state’s GDP. In the state’s ‘Women Empowerment Policy and Sustainable Development Goals Vision Document’, GRB has been highlighted as a key intervention agenda.

Figure 1 shows that budgets for GEWE ranged between 2% and 5% of Bihar’s GDP from 2009-10 to 2019-20. Moreover, while the overall state budget estimates increased over a range of 3-27% during this period, gender budget estimates appear to have increased only minimally. Out of 20 departments that report in the GBS, the largest proportion of gender budgets have been consistently allocated by the departments of Rural Development, Education, Social Welfare, and Health. Overall, gender budgets from these four departments contribute 80% of the total gender budget estimates. About half of the departments reporting in the GBS contribute less than 1% each to overall GBS.

Figure 1. Percentage of gender budget allocations in Bihar’s GSDP (Gross State Domestic Product)

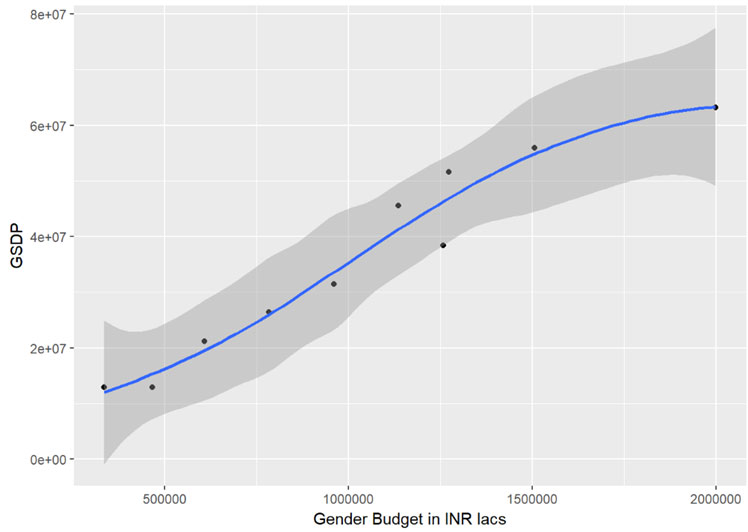

The growing trend of gender budget percentage to overall state’s GDP is established with a strongly positive linear correlation (of 0.967) between the state’s GDP and GEWE budgets, as shown in Figure 2. Although not surprising, the correlation conveys a strongly positive relationship between gender budgets and the state’s selected fiscal attributes. We use this statistic to provide further credence to the work of feminist economists that locates gender within the larger macroeconomic and fiscal space.

Figure 2. Linear correlation between GSDP and gender budget allocations

Since the GBS does not report corresponding output results against gender budget allocations, it is nearly impossible to map what is actually being spent against what is budgeted. Non-availability of gender statistics, like sex-disaggregated data, further constraints tracking what actually reaches women and girls. To take an example, we undertook an exercise of extrapolating gender outputs for select public welfare schemes, merely illustrative in nature, to reason that the number of female beneficiaries to total beneficiaries may be underrepresented based on the actual beneficiary population.

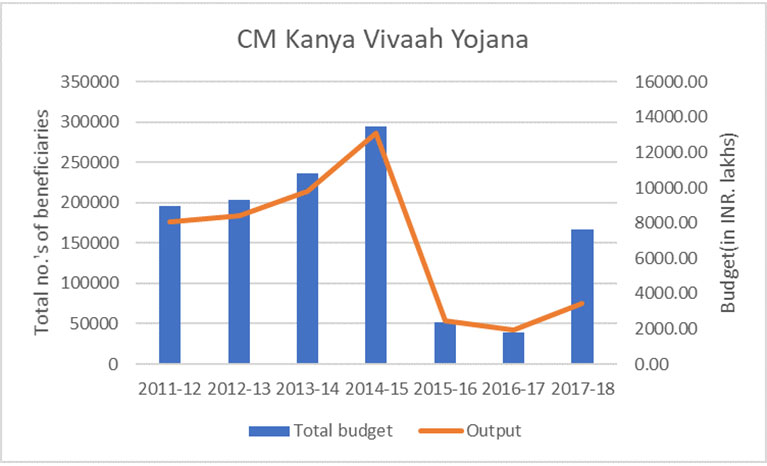

One of the flagship schemes of the state government is the Chief Minister’s Marriage Scheme for Girls (Mukhya Mantri Kanyya Vivaah Yojana) where Below Poverty Line (BPL) as well as those households with an annual income of up to Rs. 60,000 are given a one-time amount of Rs. 5,000 during the time of marriage of an adult daughter (at least 18 years or over) in the family. The amount is deposited by direct benefit transfer in the name of marriageable daughter. Output data for the scheme are not disaggregated by intersectional axes of caste, religion, urban/rural geography, and disability.

Although the scheme is targeted at declining the prevalence of child marriage and increasing the number of registered marriages, since the cash transfer is made in the girl’s name, the scheme might otherwise perpetuate dowry system by upholding patriarchal social and cultural norms. Figure 3 shows that the scheme’s budget was the largest in 2014-15 and smallest in 2016-17, with the corresponding number of beneficiaries declining sharply (by 85%) from 287,063 to 42,739.

Figure 3. Gender budgets and gender outputs for Kanya Vivaah Yojana (2011-12 to 2017-18)

Conclusion: Going beyond budgetary allocations to tracking GEWE outcomes through strengthening existing GRB architecture

Government of Bihar’s policy commitments on GRB are a step in the right direction. However, they do not seem to be enough to demonstrate output- and outcome-level results on GEWE. Our scrutiny of policy commitments, gender budgets, and illustrative outputs reveal that long-term investments on GEWE, as assessed through the GBS, fall short of monitoring output- and outcome-level results. A lack of institutional interventions on GRB, including the GBS, which does not account for GEWE results, presents the need for mapping out and mainstreaming a GRB architecture in the state. Accordingly, we hope that a robust GRB architecture can be operationalised at the state level and can also be adapted to the needs of governments across district and local levels. As our scrutiny of Bihar’s GRB processes and mechanisms relied heavily on the data and statistics available in the public domain, and only over a limited period of time, we hope that future inquiries on GRB can draw from our findings to build further on GRB interventions in the state, especially taking into account the role of rights-holders as well.

Courtesy : Shrijna Dixon (Independent Consultant) , Yamini Mishra (Amnesty International).