Relevance: Mains: G.S paper II: Polity: Constitution and constitutional posts

Context:

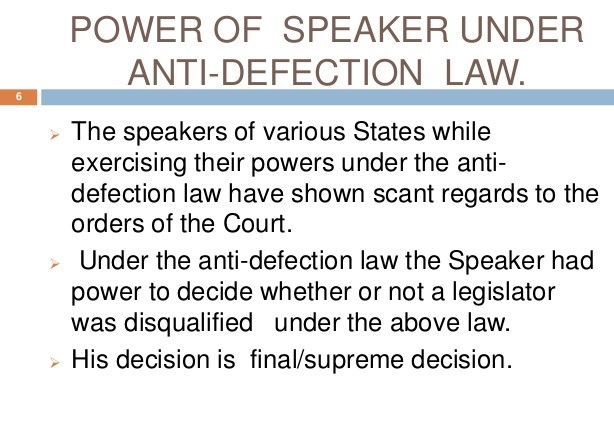

- There are two significant aspects to the Supreme Court’s latest decision on the Speaker as the adjudicating authority under the anti-defection law.

• The first is that Parliament should replace the Speaker with a “permanent tribunal” or external mechanism to render quick and impartial decisions on questions of defection.

• Few would disagree with the Court’s view that initial fears and doubts about whether Speakers would be impartial had come true.

• The second is its extraordinary ruling that the reference by another Bench, in 2016, of a key question to a Constitution Bench was itself unnecessary.

Disqualification in fixed time frame:

- The question awaiting determination by a larger Bench is whether courts have the power to direct Speakers to decide petitions seeking disqualification within a fixed time frame.

• The question had arisen because several presiding officers have allowed defectors to bolster the strength of ruling parties and even be sworn in Ministers by merely refraining from adjudicating on complaints against them.

• Some States have seen en masse defections soon after elections.

• Secure in the belief that no court would question the delay in disposal of disqualification matters as long as the matter was pending before a Constitution Bench, Speakers have been wilfully failing to act as per law, thereby helping the ruling party, which invariably is the one that helped them get to the Chair.

Case study:

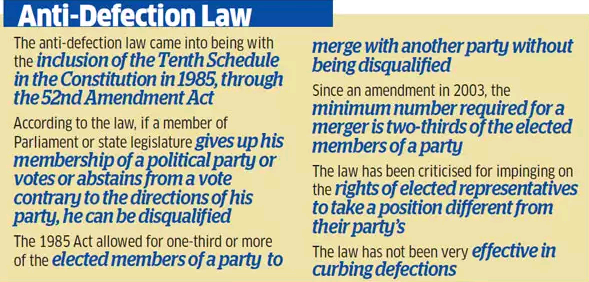

- The reference to a larger Bench, in 2016 in S.A. Sampath Kumar vs. Kale Yadaiah was based on the landmark judgment in Kihoto Hollohan (1992) which upheld the validity of the Constitution’s Tenth Schedule, or the anti-defection law.

Significance of this verdict:

- This verdict had also made the Speaker’s order subject to judicial review on limited grounds.

• It made it clear that the court’s jurisdiction would not come into play unless the Speaker passes an order, leaving no room for intervention prior to adjudication.

• Finding several pending complaints before Speakers, the Bench, in 2016, decided that it was time for an authoritative verdict on whether Speakers can be directed to dispose of defection questions within a time frame.

• While fixing an outer limit of three months for Speakers to act on disqualification petitions, in the present case, Justice R.F. Nariman given four weeks to the Manipur Assembly Speaker to decide the disqualification question in a legislator’s case. He also held that the reference was made on a wrong premise.

• He has cited another Constitution Bench judgment (Rajendra Singh Rana, 2007), in which the Uttar Pradesh Speaker’s order refusing to disqualify 13 BSP defectors was set aside on the ground that he had failed to exercise his jurisdiction to decide whether they had attracted disqualification, while recognising a ‘split’ in the legislature party.

Conclusion:

- As “failure to exercise jurisdiction” is a recognised stage at which the court can now intervene, the court has thus opened a window for judicial intervention in cases in which Speakers refuse to act.

• This augurs well for the enforcement of the law against defection in letter and spirit.