MIGRANT WORKERS: LONG-TERM ADVERSITY CONTINUES DEALING WITH SHORT-TERM COVID-19

Relevance: Sociology: Work and economic life: Formal and informal organization of work; Labour and society; Social Change in Modern Society: Agents of social change; Rural and Agrarian Social Structure:Rural and Agrarian transformation in India: Problems of rural labour, bondage, migration.Components of population growth: birth, death, migration. & G.S paper II Governance

CONTEXT

Since the nation-wide lock down on March 24th, the reverse-migration of semi-skilled and unskilled workers ‘on foot’ — from cities back to their villages — have received wide attention. Poignant, heartbreaking images are all over the media and there are reports suggesting that as many as 22 workers have died while trying to get back home.

Internal Migration Challenges

The Indian Context

Free movement is a fundamental right of the citizens of India and internal movements are not restricted.

The Constitution states “All citizens shall have the right (…) to move freely throughout the territory of India; to reside and settle in any part of the territory of India”.

Article 19(1)(d) and Article 19(1)(e), Part lll, Fundamental Rights, The Constitution of India, 1950.

India’s total population, as recorded in the recently concluded Census 2011, stands at 1.21 billion. Internal migrants in India constitute a large population2: 309 million internal migrants or 30 per cent of the population (Census of India, 2001), and by more recent estimates 326 million or 28.5 per cent of the population (NSSO 2007–08).

Lead source states of internal migrants include Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha, Uttarakhand and Tamil Nadu, whereas key destination areas are Delhi, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Haryana, Punjab and Karnataka.

There are conspicuous migration corridors within the country: Bihar to National Capital Region, Bihar to Haryana and Punjab, Uttar Pradesh to Maharashtra, Odisha to Gujarat, Odisha to Andhra Pradesh and Rajasthan to Gujarat (UNESCO/UNICEF, 2012b).

Further, internal migration remains grossly underestimated due to empirical and conceptual difficulties in measurement. Despite the fact that approximately three out of every ten Indians are internal migrants, internal migration has been accorded very low priority by the government, and existing policies of the Indian state have failed in providing legal or social protection to this vulnerable group.

This can be attributed in part to a serious data gap on the extent, nature and magnitude of internal migration. Migration in India is primarily of two types: (a) Long-term migration, resulting in the relocation of an individual or household and

(b) Short-term or seasonal/circular migration, involving back and forth movement between a source and destination. Estimates of short-term migrants vary from 15 million (NSSO 2007–2008) to 100 million (Deshingkar and Akter, 2009).

Internal migration patterns and dynamics intersect with two developments in India’s current human development context.

First, rapid urbanisation and the growth of second tier cities and towns: increased levels of migration cause cities to face many socio-economic and environmental challenges that exacerbate urban poverty and intensify inequalities in access to income and services, and thereby deepen social exclusion.

Second, the expansion of rights based approaches – increasingly enshrined in law – to ensure that basic services are accessible to all citizens is a process in the making, transforming India’s social policy landscape from welfarism to rights-based development.

Due to the lack of analytical refinement in the way that internal migration is defined, design and delivery of services for migrants is hampered.

Migrants continually face difficulties in becoming a full part of the economic, cultural, social and political lives of society. Regulations and administrative procedures exclude migrants from access to legal rights, public services and social protection programmes accorded to residents, on account of which they are often treated as second-class citizens.

Internal migrants face numerous constraints, including: a lack of political representation; inadequate housing and a lack of formal residency rights; low-paid, insecure or hazardous work; limited access to state-provided services such as health and education; discrimination based on ethnicity, religion, class or gender; extreme vulnerability of women and children migrants to trafficking and sex exploitation (UNESCO/ UN-HABITAT, 2012).

Internal migrants, especially seasonal and circular migrants, constitute a “floating” population, as they alternate between living at their source and destination locations, and in turn lose access to social protection benefits linked to the place of residence.

There remains no concerted strategy to ensure portability of entitlements for migrants (Deshingkar and Farrington, 2009). Planning for migrant families who are not settled but on the move warrants a fundamental rethinking of development approaches and models (Smita, 2007).

Understanding Internal Migrants’ Exclusion

Migrants are looked upon as ‘outsiders’ by the local host administration, and as a burden on systems and resources at the destination. In India, migrants’ right to the city is denied on the political defence of the ‘sons of the soil’ theory, which aims to create vote banks along ethnic, linguistic and religious lines.

Exclusion and discrimination against migrants take place through political and administrative processes, market mechanisms and socio-economic processes, causing a gulf between migrants and locals (Bhagat, 2011).

This leads to marginalisation of migrants in the decision-making processes of the city, and exacerbates their vulnerabilities to the vagaries of the labour market, poverty traps, and risks of discrimination and violence.

Women migrants face double discrimination, encountering difficulties peculiar to migrants, coupled with their specific vulnerability as victims of gender-based violence, and physical, sexual or psychological abuse, exploitation and trafficking.

Migrants are further marginalised through negative portrayal in the media, and stigmatisation by municipal and state leaders who exploit communal divides and prejudices.

Myths and Facts about Internal Migration

A fundamental misunderstanding and lack of recognition of the migratory phenomenon is increasingly at the root of misconceived policies or stubborn inaction regarding internal migration.

Policies and programmes facilitating migrant integration at the destination remain weak at best or non-existent.

Further, migrants are subjected to hate propaganda from local fundamentalists who, motivated by fear and parochialism, blame them for all civic and social unrest at the destination. Clear and consistent data on migration is urgently required to dispel myths and mis-understanding about internal migrants, as displayed on the opposite page. Benefits of Migrants’ Inclusion in Society“In our increasingly diverse societies, it is essential to ensure harmonious interaction among people and groups with plural, varied and dynamic cultural identities as well as their willingness to live together. Policies for the inclusion and participation of all citizens are guarantees of social cohesion, the vitality of civil society and peace.”

From Article 2, UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity, 2001 Internal migration is an integral part of development and cities are important destinations for migrants.

The rising contribution of cities to India’s GDP would not be possible without migration and migrant workers. Some of the important sectors in which migrants work include: construction, brick kiln, salt pans, carpet and embroidery, commercial and plantation agriculture and variety of jobs in urban informal sectors such as vendors, hawkers, rickshaw puller, daily wage workers and domestic work (Bhagat, 2012).

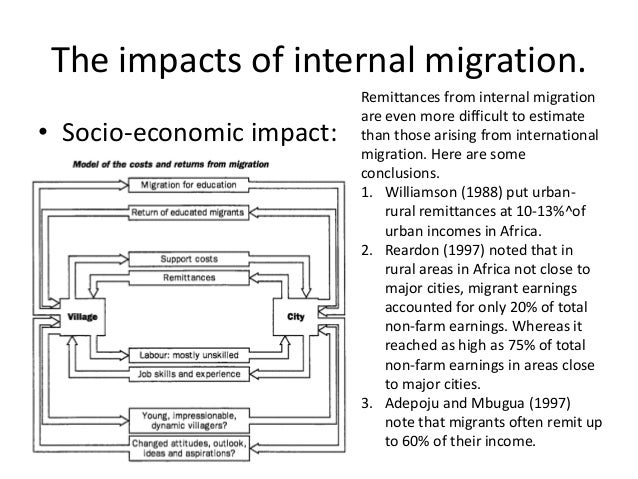

Estimates of the domestic remittance market are roughly USD 10 billion for 2007-08 (Tumbe, 2011). Evidence reveals that with rising incomes, migrant remittances can encourage investment in human capital formation, particularly increased expenditure on health and, to some extent, on education (Deshingkar and Sandi, 2012).

Many positive impacts of migration remain unrecognised.

Migrants are indispensable and yet invisible key actors in socially dynamic, culturally innovative and economically prosperous societies.

An independent study examining the economic contribution of circular migrants based on major migrant employing sectors in India revealed that they contribute 10 per cent to the national GDP (Deshingkar and Akter, 2009).

In particular, women migrants’ , Social Inclusion of Internal Migrants in India contribution at the destination remains unacknowledged, despite the fact that they shoulder the double burden of livelihood (being often engaged as unregistered, unpaid and therefore invisible workers) and household work, in the absence of traditional family-based support systems.

Migrants bring back to source locations a variety of skills, innovations and knowledge, known as ‘social remittances’, including changes in tastes, perceptions and attitudes, such as for example, a lack of acceptance of poor employment conditions, low wages and semi-feudal labour relationships, and improved knowledge and awareness about workers’ rights (Bhagat, 2011).

Migration may provide an opportunity to escape caste divisions and restrictive social norms, and work with dignity and freedom at the destination (Deshingkar and Akter, 2009).

Women left behind enjoy empowerment effects, with increased interaction in society, including their participation as workers and as household decision-makers (Srivastava, 2012a).

Internal migration can expand people’s freedoms and capabilities, and make substantial contributions to human development in terms of improved incomes, education and health (UNDP, 2009).

For more such notes, Articles, News & Views Join our Telegram Channel.

Click the link below to see the details about the UPSC –Civils courses offered by Triumph IAS. https://triumphias.com/pages-all-courses.php