Effective contract enforcement is the key for the formation and expansion of business enterprises. But how does improvement in court performance matter differently to different caste groups? This article shows that the benefit of an efficient judiciary is higher for first-time entrepreneurs within communities that lack traditional informal business networks. This implies that besides other factors, improvements in court quality can be instrumental in enhancing social mobility.

Do courts matter for the growth of businesses in India; and if they matter, are they more relevant for some social groups compared to others? These two questions form the core of our research agenda. While there has been some attempts to answer the first question (Amirapu 2015, Chemin 2009, 2010, Rao 2020), we have not come across any attempt to answer the second. Understanding the rationale behind the second hypothesis – courts help different castes differently – requires an understanding of formal and informal ways of dispute resolution. When court procedures are costly, people often approach community organisations for resolving disputes. Such organisations often use social sanction as the means for enforcing contracts – if an individual named x cheats a member of community A, no one from community A will do business with x. Whether this punishment is good enough to keep x honest depends on how important community A’s business is for x. Among other factors, the proportion of community A people in the business world is probably most critical in determining the bite of the punishment. If, for example, 80% of the business people come from community A, x would be in serious trouble by cheating a member of community A. In this context, how do the improvements in court performance matter differently to different caste groups?

Do courts help different castes differently?

Informal dispute resolution mechanisms are costless, and therefore, business-majority castes who can use this informal mechanism effectively will not approach courts for dispute resolutions. It is the business-minority castes that, without access to any effective informal dispute resolution mechanism, will benefit from improved courts. Let us take a hypothetical example to illustrate this point. Suppose informal dispute resolution mechanism of business-majority castes takes three months to resolve a dispute. Let us assume that in the least congested court, it takes a year and in a highly congested court, it takes 10 years to resolve the same dispute. Even if the court improves to resolve all the disputes in a year, the business-majority castes are not likely to benefit as their informal mechanism can do the same in three months. It is the business-minority castes that will benefit from improved courts.

If we bring this example to our research question, it is safe to infer that entrepreneurs from bigger business communities are less affected by the quality of the court – they can enforce contracts at much lower cost using their networks. A corollary from this deduction tells us that entrepreneurs who belong to under-represented communities in business, are more likely to benefit from improved courts.

But which groups are under-represented in the Indian business? We treat Scheduled Castes and Tribes (SC/STs) as the minority in the Indian business, which is consistent with the very low proportion of SC/ST entrepreneurs observed in the Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprise Survey (MSME) of registered firms. We conjecture that SC/ST entrepreneurs will benefit more from improved courts than other entrepreneurs from castes that lie above SC/STs in the traditional caste ladder. For simplicity, we refer to the latter group as upper castes. We test this hypothesis in our research (Chakraborty et al. 2017), using entrepreneurial data from the 2007 MSME survey.1

The data

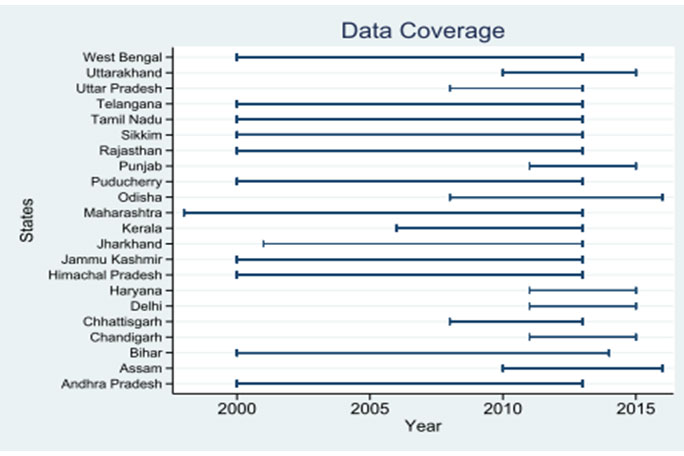

In addition to combining the issues of economic success, caste identity, and quality of judicial institutions, an important contribution of our research is constructing a district court-level panel data2 on judicial efficiency in India. The data come from the records of each district court regarding their filing, pendency, and disposal of civil cases between 2001 and 20163. While we approached the high courts across all the states of India, there was a significant variation in the data that we received from each of these states. The coverage of our final data is given in the figure below.

Figure 1. Availability of administrative records across states and over time

The data we have collected include, for each district-year pair, the number of cases pending, the number of cases disposed of, and the number of cases initiated. Using this information, we constructed a measure of court inefficiency, known as the ‘duration index’. At any point of time, it measures the number of years it will take to clear the entire backlog of pending cases if no new cases are admitted in the court after year t and the rate of solving cases remain the same going forward.

The data we have collected include, for each district-year pair, the number of cases pending, the number of cases disposed of, and the number of cases initiated. Using this information, we constructed a measure of court inefficiency, known as the ‘duration index’. At any point of time, it measures the number of years it will take to clear the entire backlog of pending cases if no new cases are admitted in the court after year t and the rate of solving cases remain the same going forward.

Formally, the index is measured as: δit=(pit+ fit)/dit

In this expression, δit represents the duration index for court i in year t; pit represents the number of cases pending at the beginning of the year t in court i; fit represents the number of cases filed during year t in court I; dit represents the number of cases disposed during year t in court i. A higher value of the duration index indicates lower efficiency of courts.

Findings

Why would court quality affect business outcomes? We argue that if the court quality is better in the year the business was established, and in the district where the business is located, entrepreneurs are more confident about the contract enforcement in the future, and they will make more long-term investments. Specifically, we look at two variables that, in our view, capture such investments: (i) whether a firm formally registers its business in the year of inception, and (ii) whether it is a manufacturing unit. The process of formal registration involves some costs, but more importantly, after registration the firm is supposed to follow certain rules and regulations, which are costly. Similarly, manufacturing requires large set-up costs, which are difficult to recover in case the firm decides to shut down within a short period of time. This is also supported by the MSME survey. We find that the average value of plant and machinery for a manufacturing firm is Rs. 280,559 (approximately US$4,000). In comparison, for non-manufacturing firms, the corresponding number is only Rs. 34,034 (approximately US$486).

For our analysis, we merge the district-level court data with the firm-level information obtained from the MSME survey. We find that districts where courts are more efficient, SC/ST entrepreneurs are more likely, than their upper-caste counterparts, to register their business in the year of their inception. They are also more likely to set up manufacturing units.

However, our conjecture that SC/ST groups are business minorities, and therefore benefit more from improved courts, may not hold in certain areas where they either form a large share of population or have political power. In those areas, SC/ST entrepreneurs may run an informal dispute resolution mechanism, and may not benefit from improved courts. To test this possibility, we divide all districts into two groups: if a district’s SC/ST population proportion is higher than the country-level SC/ST proportion, we call it a ‘high (SC/ST) district’, otherwise, we call it a ‘low (SC/ST) district’. We find that the improved courts help SC/ST entrepreneurs more only in low (SC/ST) districts, where SC/ST network is presumably weak. In districts where the proportion of SC/ST is high, SC/ST entrepreneurs do not benefit more than the upper-caste entrepreneurs from a more efficient judiciary.

For probing this result further, we next divide the districts into two groups based on political reservation: districts where at least one state assembly constituency is reserved for SC/STs, and districts where none of the seats are reserved. We expect that courts will help SC/ST entrepreneurs more where they are politically weaker or less connected, that is, in non-reserved districts. Our results confirm this expectation – SC/ST entrepreneurs benefit more from improved courts only in non-reserved districts.

Discussion

In sum, we interpret our findings as formal courts substituting for the lack of informal community networks or socio-political connectedness. However, an alternate interpretation could be that of social hierarchy. Formal institutions might be more beneficial to marginalised groups because they are traditionally lower down in the social ladder, and whenever a dispute breaks out between an SC/ST and an upper-caste entrepreneur, the traditional dispute resolution bodies always side with the social elite. To understand this further, we next study the difference between entrepreneurs from Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and general categories (castes which are above OBCs and do not enjoy any benefit of affirmative action policies). While OBCs are traditionally at a social disadvantage compared to castes clubbed in the upper-caste category, they are well-represented among entrepreneurs. For instance, they constitute around half of the entrepreneurs in the MSME data. Hence, compared to the general categories, OBCs are behind in social hierarchy but ahead in network size. We do not find any differential impact of improved courts on OBC entrepreneurs compared to entrepreneurs in the general category.

Judicial delay in India is well-reported in the popular media. That improvements in the court system can benefit business has also been the focus of a few academic studies in recent years. We go a step further and show that the marginal benefit of an efficient judiciary is even higher for first-time entrepreneurs within communities that lack traditional informal business networks. This implies that besides other factors, improvements in court quality can be instrumental in enhancing social mobility.

Notes:

- This study is funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC).

- Panel data (also known as longitudinal data) is a dataset in which multiple entities are observed across time.

- While we requested all states for data up to 2013, some states provided the data until the latest year available.